Wikimedia Commons/Graveyardwalker

Clotilda Survivors Build America’s Last African-Founded Community

The Clotilda slipped into Mobile Bay on July 9, 1860, with 110 West Africans on board. They were the last people ever smuggled into America as slaves, thanks to Captain Meaher’s illegal bet.

After the Civil War ended, these freed men and women asked to go home to Africa. When told no, they did something bold instead.

In 1866, thirty-two survivors pooled their cash and bought land near Mobile. Soon, Africatown took shape with its own rules, Yoruba language, and African ways.

Under leaders like Cudjo Lewis, they built homes, a church, and later a school that grew into the backbone of Black education in Mobile.

This remarkable community still stands today as a testament to what freedom truly means.

Shutterstock

A Rich Businessman Made an Illegal $1,000 Bet

Timothy Meaher, a rich Mobile landowner and boat captain, bet $1,000 in 1859 that he could sneak enslaved Africans into Mobile Bay. He made this bet even though the slave trade had been banned since 1808.

Meaher wagered during a boat trip when Northern travelers talked about ending cross-border slave trading.

Earlier, Meaher backed pro-slavery efforts, giving ships to William Walker for Central American takeover attempts in 1858. His bet showed his greed and disregard for federal law right before the Civil War.

Wikimedia Commons

The Ship That Carried the Last Enslaved Africans to America

Meaher hired Captain William Foster to fix up the Clotilda, a two-masted boat built for lumber trade in 1855 at Meaher’s Mobile shipyard.

The 86-foot vessel with its copper-covered bottom left Mobile on March 4, 1860, heading for West Africa. Foster might have used the ship before for illegal slave trading between Cuba and American Gulf ports.

Unlike typical shallow-water Gulf boats, the Clotilda had a deep hull perfect for long ocean trips across the Atlantic.

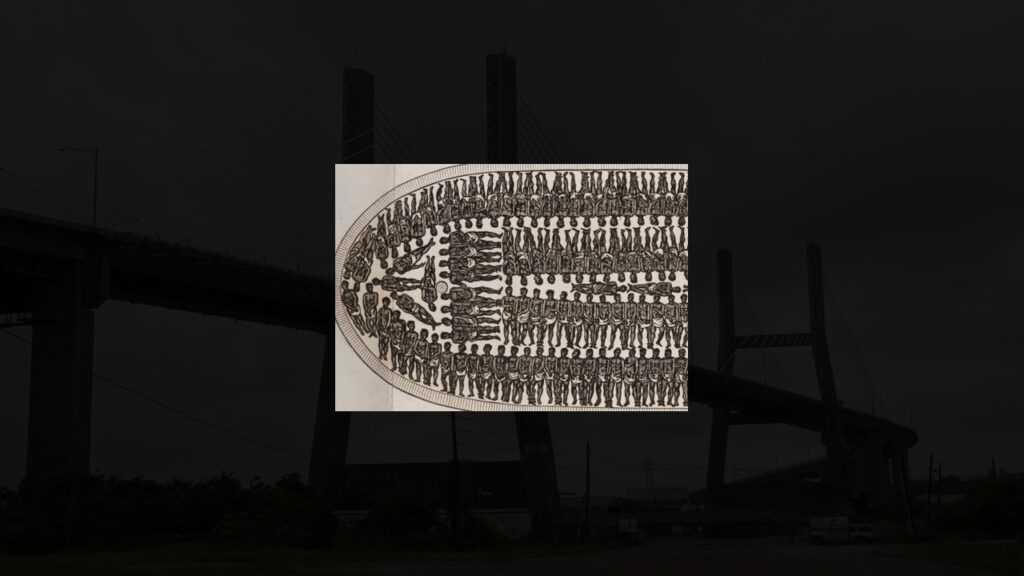

Wikimedia Commons/Printed for J. Hatchard and son, London, 1825

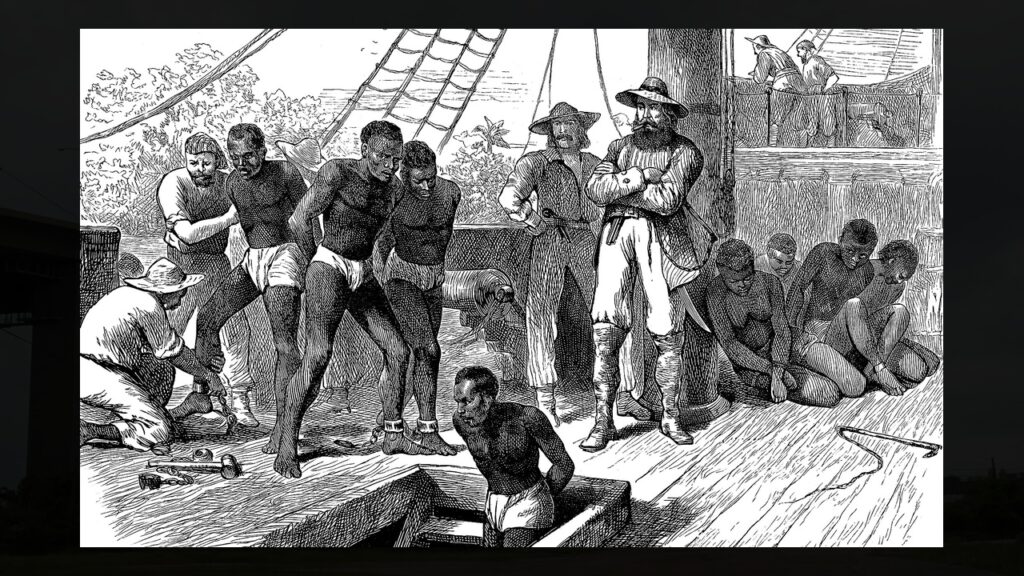

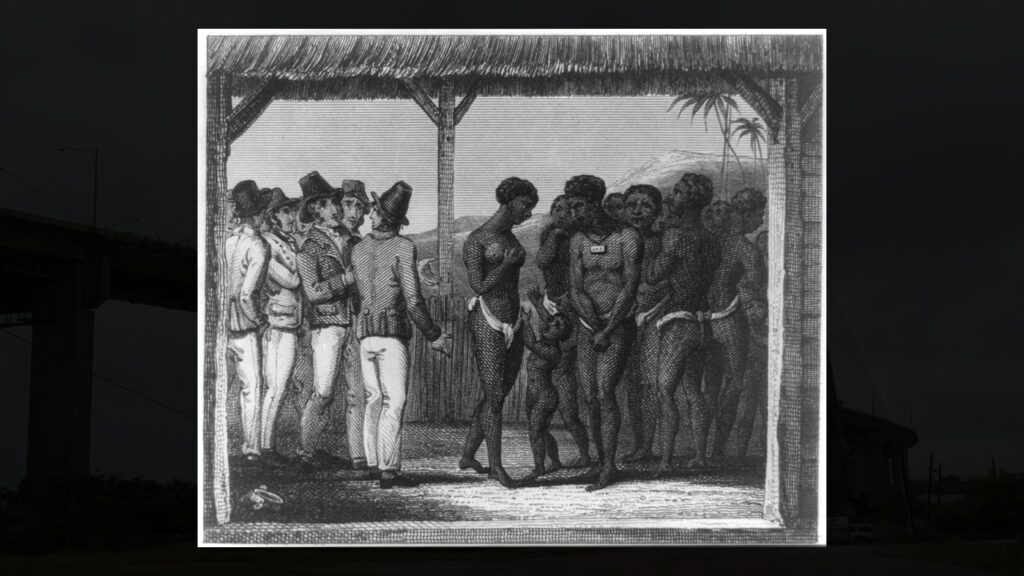

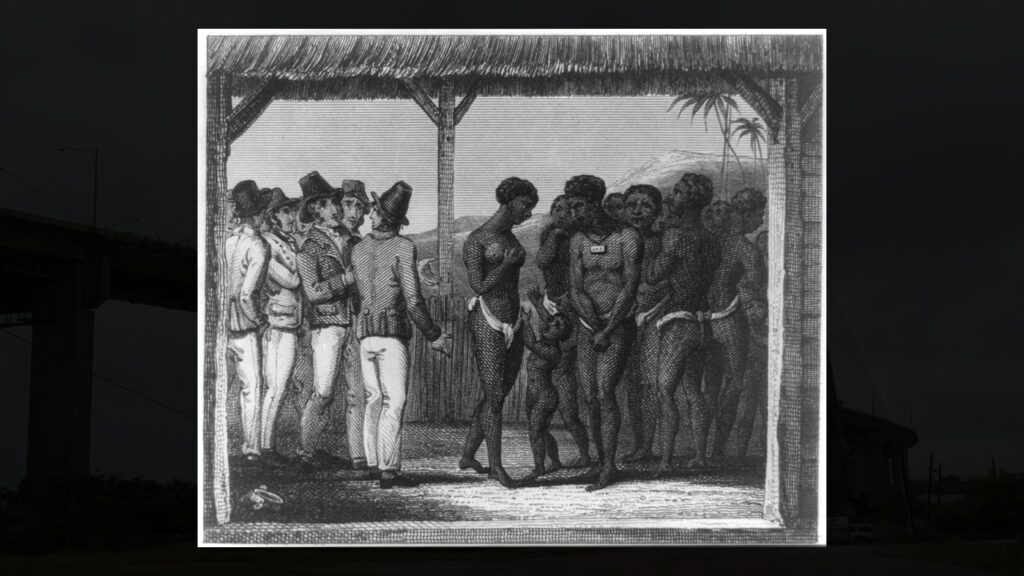

West Africans Were Torn From Their Homes

Foster reached the slave port of Ouidah (now in Benin) after 10 weeks at sea. There, he bought 110 men, women, and children from King Dahomey for $9,000 in gold.

The captives, aged 5 to 23, came from different West African groups like Yoruba, Isha, Nupé, Dendi, Fon, Hausa, and Shamba peoples. Many were caught during Dahomean army raids on nearby villages.

Survivors later told stories of dawn attacks that wiped out whole families. In 1860 Alabama markets, these people were worth more than 20 times what Foster paid.

Wikimedia Commons/Jbolden030170

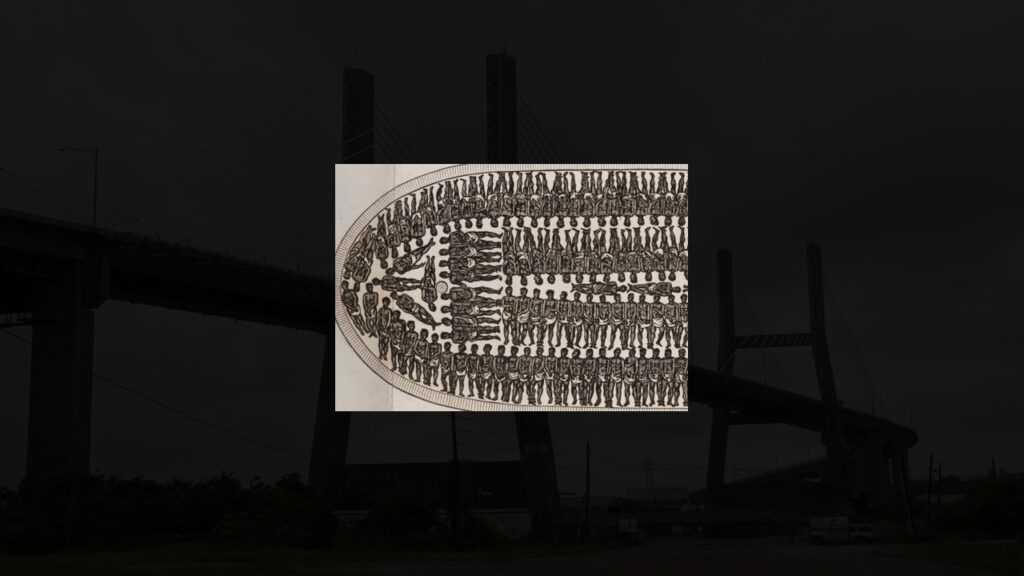

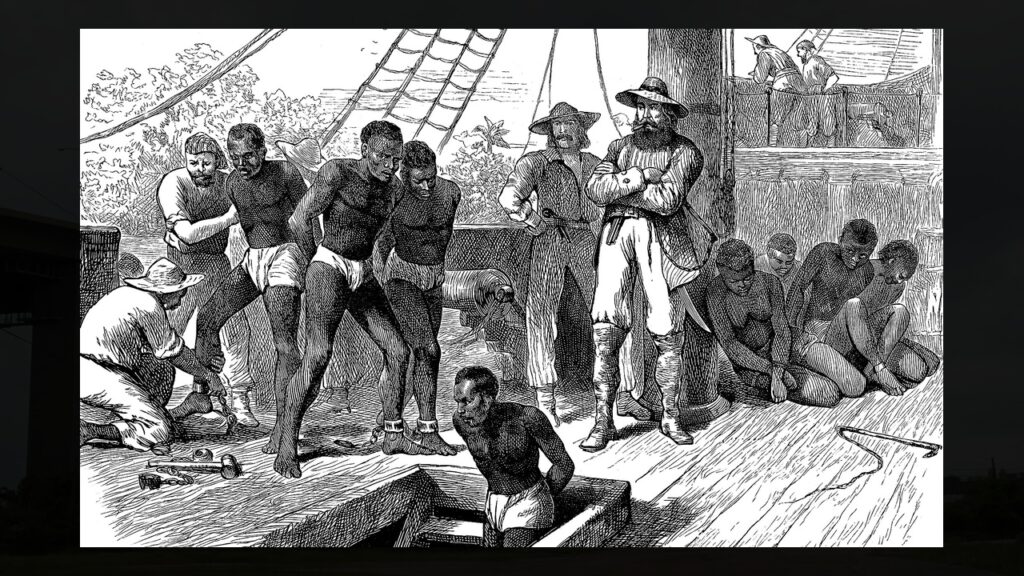

The Brutal Journey Across the Atlantic

The Clotilda took six brutal weeks to cross the Atlantic with 110 Africans crammed into the ship’s hold. One young girl reportedly died during the trip, leaving 109 survivors to reach American shores.

On July 9, 1860, the ship dropped anchor off Point of Pines in Grand Bay, near where Mississippi meets Alabama, arriving in darkness.

Foster traveled over land to meet Meaher while the ship stayed hidden offshore to avoid getting caught by federal officers.

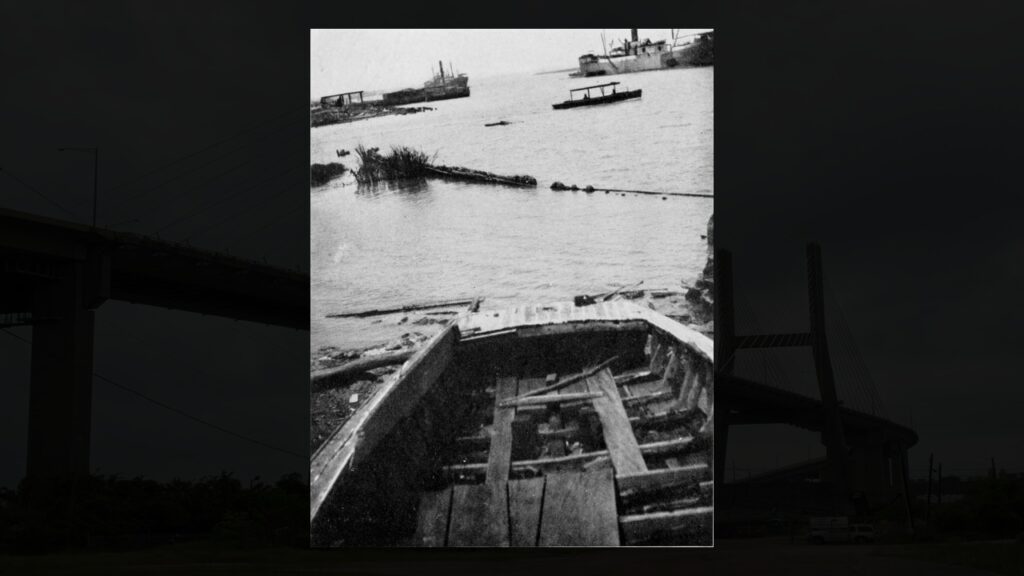

Wikimedia Commons

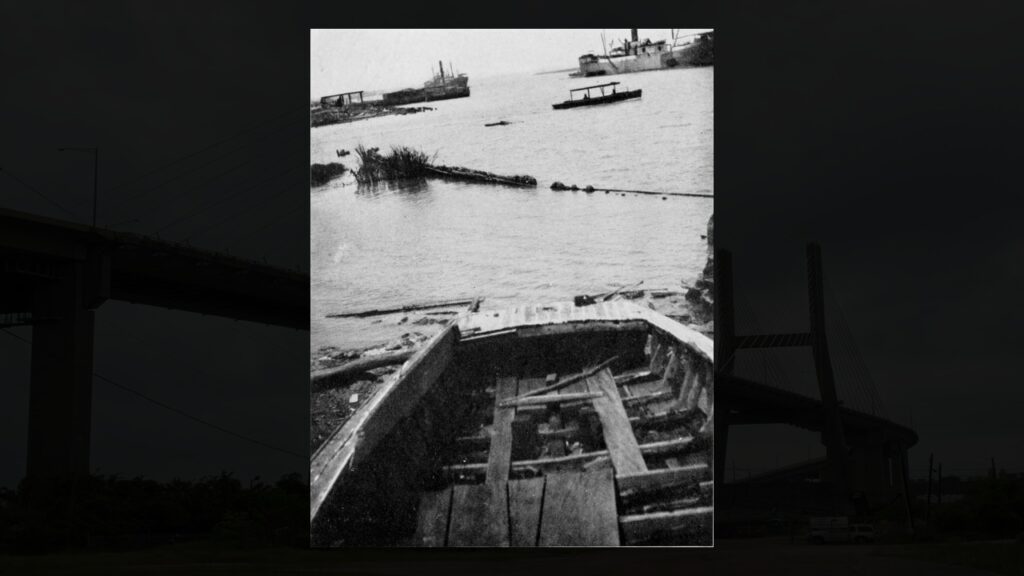

Burning the Evidence to Avoid Getting Caught

Foster brought the Clotilda into Mobile Bay at night and moved the African captives to another Meaher boat at Twelve Mile Island.

To get rid of proof from the illegal trip, Foster loaded the boat with firewood and burned it “to the water’s edge” before sinking it in the Mobile River.

The crew got paid and told to go back North while the captives were split among the people who funded the trip.

Timothy Meaher kept 30 captives on his plantation north of Mobile, including Oluale Kossola, later known as Cudjo Lewis.

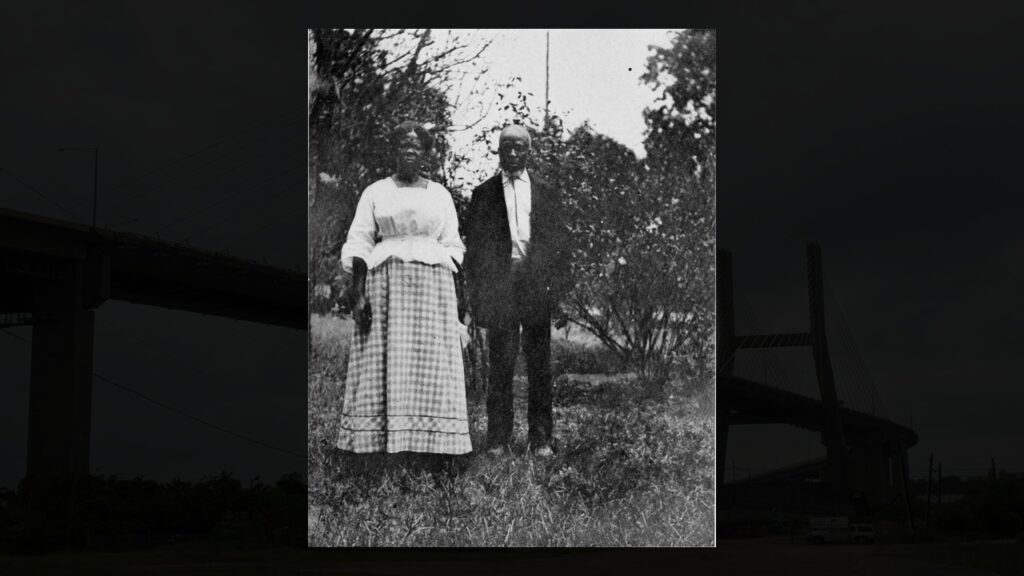

Wikimedia Commons/Emma Langdon Roche

Life Changed Overnight for the Africans

The Clotilda survivors worked on various farms around Mobile, with many serving the Meaher family and their friends until 1865.

Unlike American-born enslaved people, these Africans clearly remembered freedom and their homeland cultures during their short time in bondage.

They kept speaking their native languages, especially Yoruba, and practiced their cultural traditions while adjusting to plantation life in Alabama.

When Union forces came to Mobile in April 1865, they freed the survivors after just five years in slavery.

Shutterstock

Dreams of Going Home Were Crushed

After gaining freedom, the Clotilda survivors asked the government to help them get back to West Africa, but officials said no.

Without money for the costly ocean journey, they faced the hard truth that they would never see their homeland or families again.

Many survivors first stayed on or near their former plantations, working for wages while saving money and planning their next steps.

Wikimedia Commons/Graveyardwalker

They Bought Land From Their Former Enslaver

About 32 of the 110 original survivors pooled their small savings in 1866 to buy land from the Meaher family at Magazine Point and Plateau, three miles north of Mobile.

They paid for the land with money earned from selling vegetables, working in fields and mills, and other jobs after getting their freedom.

They called their new settlement Africatown, showing their wish to recreate African community structures on American soil.

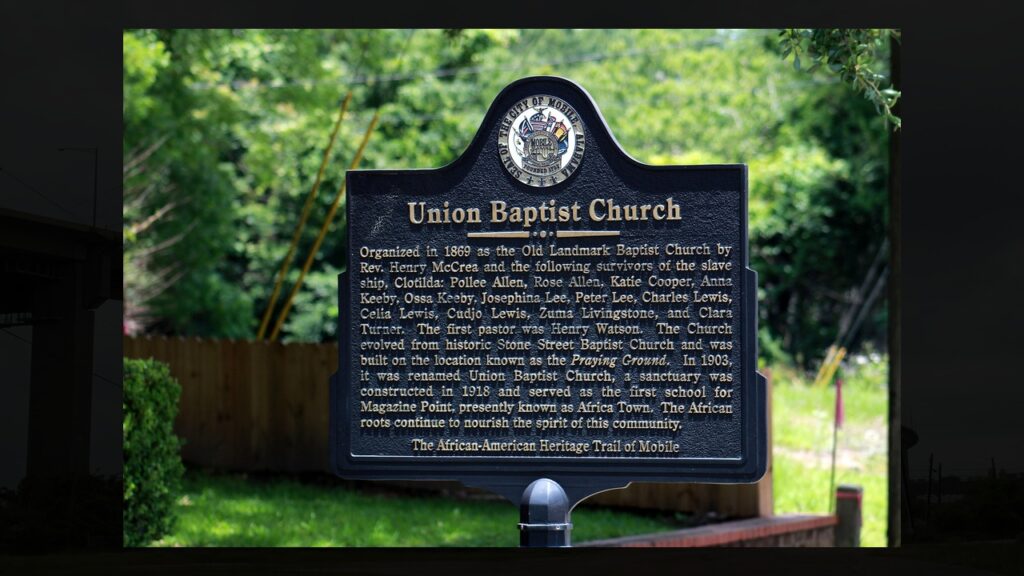

Wikimedia Commons/Graveyardwalker

African Traditions Took Root in Alabama Soil

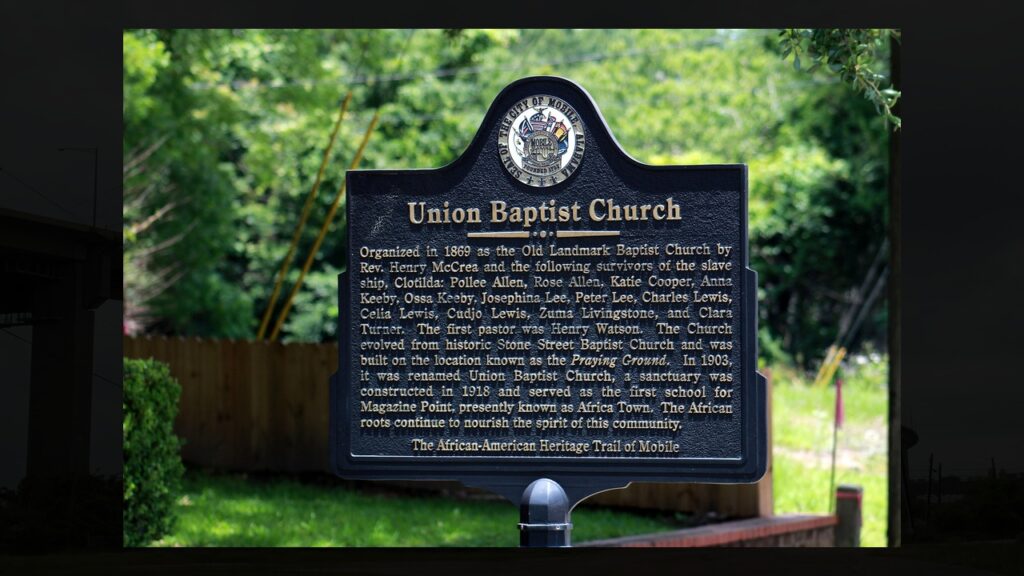

The settlers built homes, started Union Baptist Church in 1869 as their spiritual center, and created their own system of laws and leadership.

They kept African cultural practices alive, spoke Yoruba language, and organized community life around traditional social structures including a chief system.

By the 1870s, Africatown had grown into a thriving, self-sufficient community with its own businesses, craftsmen, and farms.

Wikimedia Commons/Graveyardwalker

A School Started in a Church Basement

Community elders opened “The Plateau Normal and Industrial Institute for the Education of the Head, Heart and Hands of the Colored Youth” at Union Baptist Church in 1880.

The school moved several times before 1910, when it became part of the Mobile County public school system as Mobile County Training School (MCTS). Isaiah J. Whitley became the first principal in 1910, turning it into Alabama’s first state-approved training school for Black students and Mobile’s first Black public high school.

Wikimedia Commons/Graveyardwalker

The Last African-Founded Town Leaves a Lasting Mark

Mobile County Training School became the heart of Black education in Mobile. By 1970, its graduates had founded and led practically every other Black high school in the city.

The school got state approval in 1926 under Dr. Benjamin Baker’s leadership.

In 1934, it became the only Black school in Mobile County recognized by the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools.

By the 1920s, Africatown had grown to about 1,500 residents, making it one of the largest communities in America run by African Americans. Today, roughly 100 descendants of the original settlers still live in the area.

Wikimedia Commons/Altairisfar

Visiting Mobile City Hall, Alabama

Mobile City Hall at 111 South Royal Street houses exhibits about Africatown’s founding by 32 formerly enslaved West Africans who pooled resources to buy land and create America’s last African-founded community.

Admission costs $14 for adults, $12 for seniors, military, and students, with kids under 5 free. You can visit Monday-Saturday 9am-5pm and Sunday 1-5pm.

Your ticket also gets you into Colonial Fort Conde and special exhibitions.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

Illinois4 days ago

Illinois4 days ago

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days ago

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days ago

Minnesota2 days ago

Minnesota2 days ago

Indiana4 days ago

Indiana4 days ago

Kentucky4 days ago

Kentucky4 days ago

Maryland3 days ago

Maryland3 days ago

Illinois4 days ago

Illinois4 days ago