California

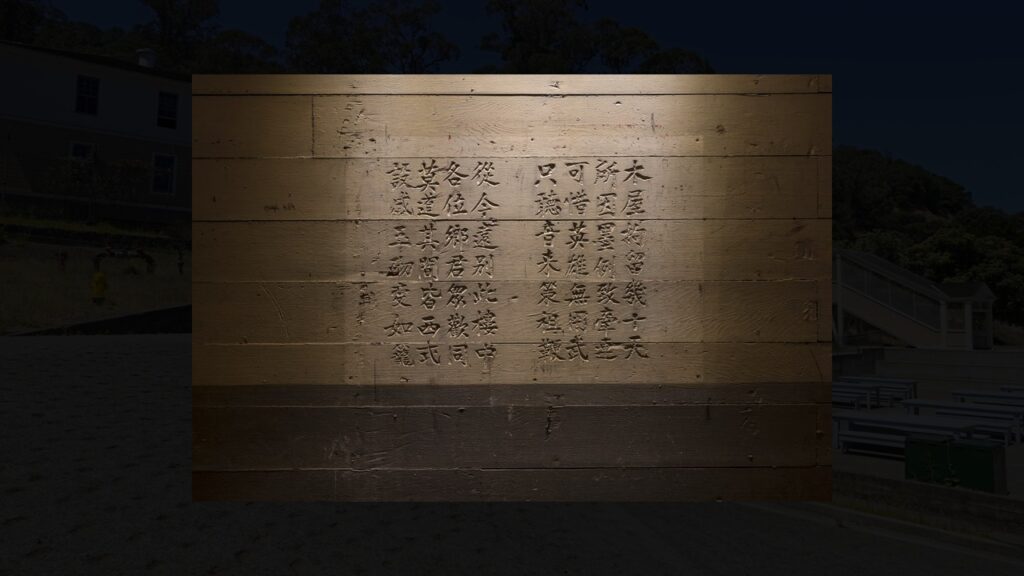

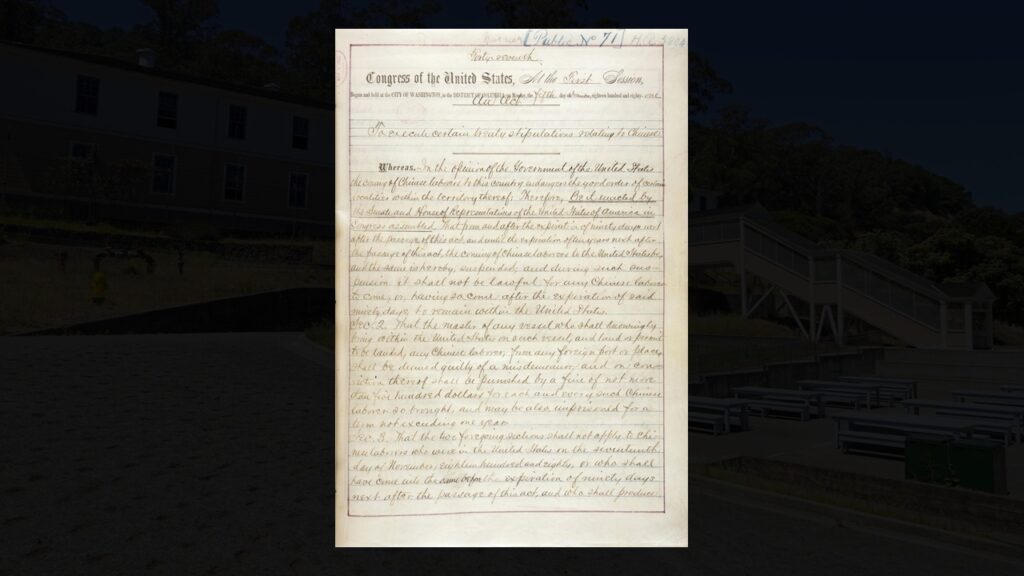

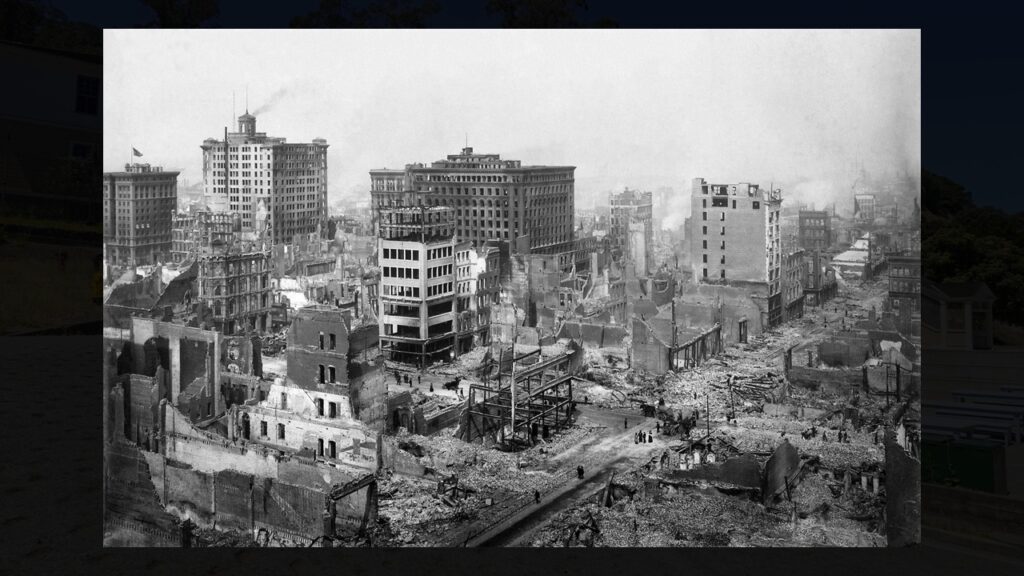

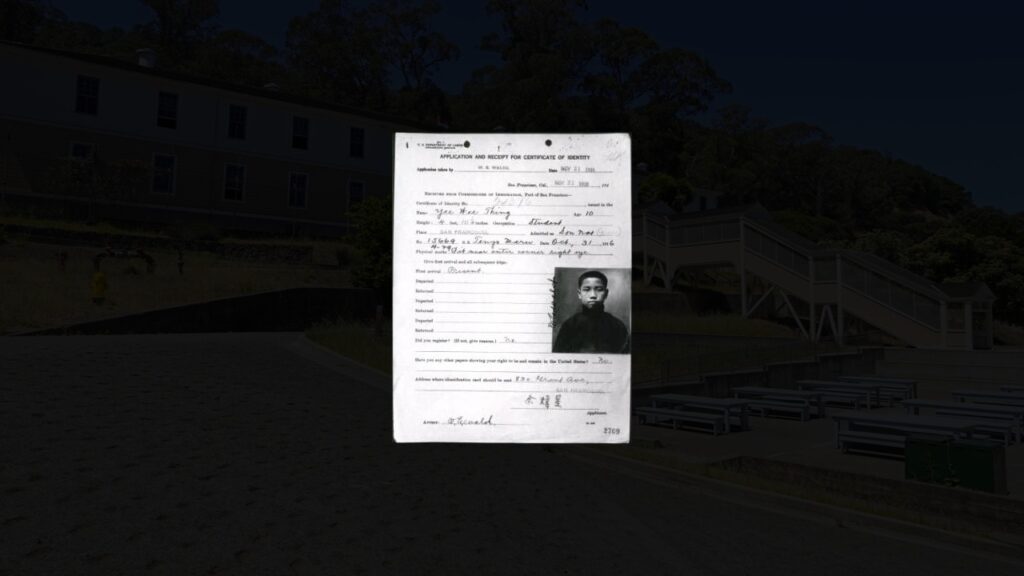

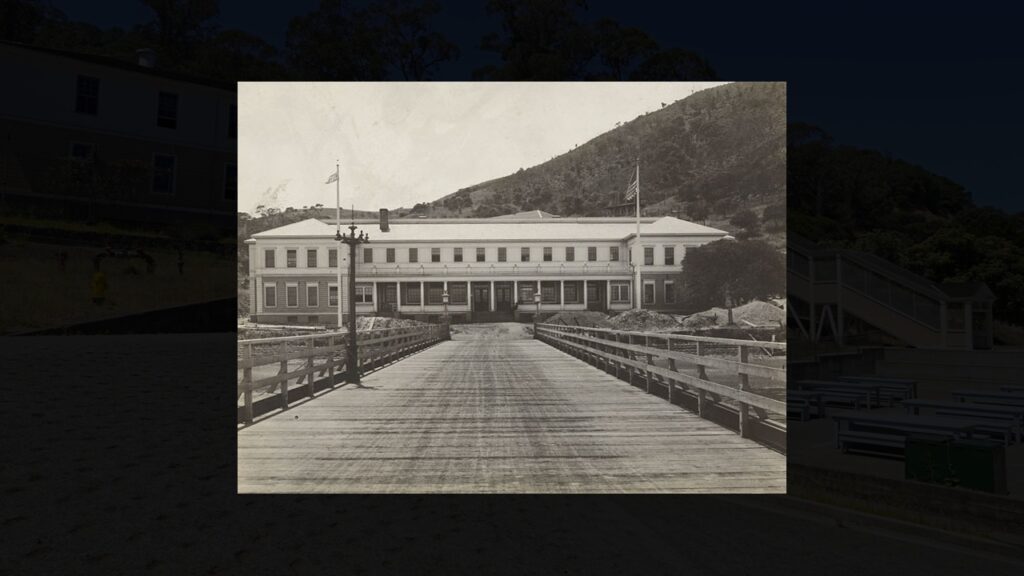

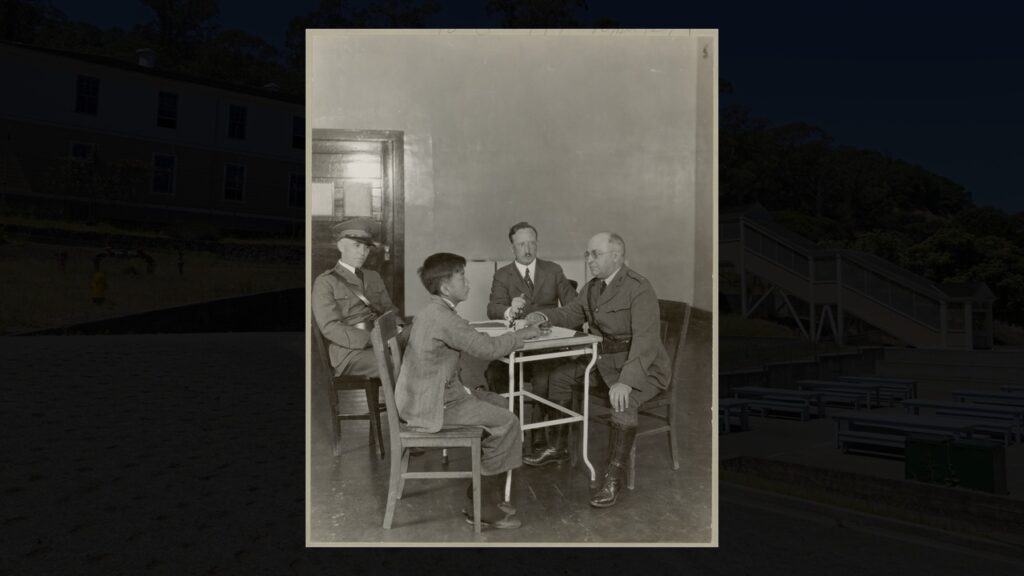

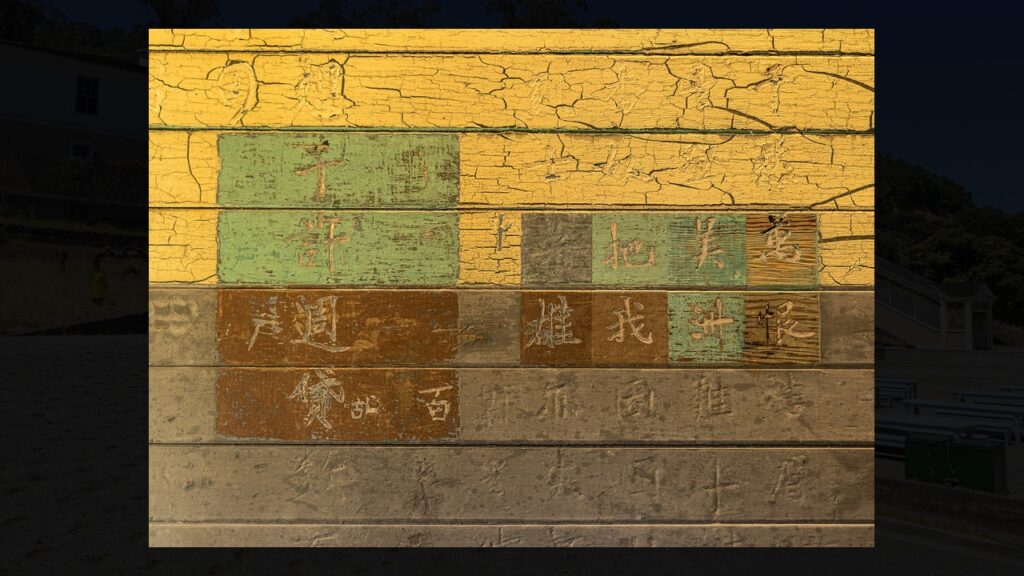

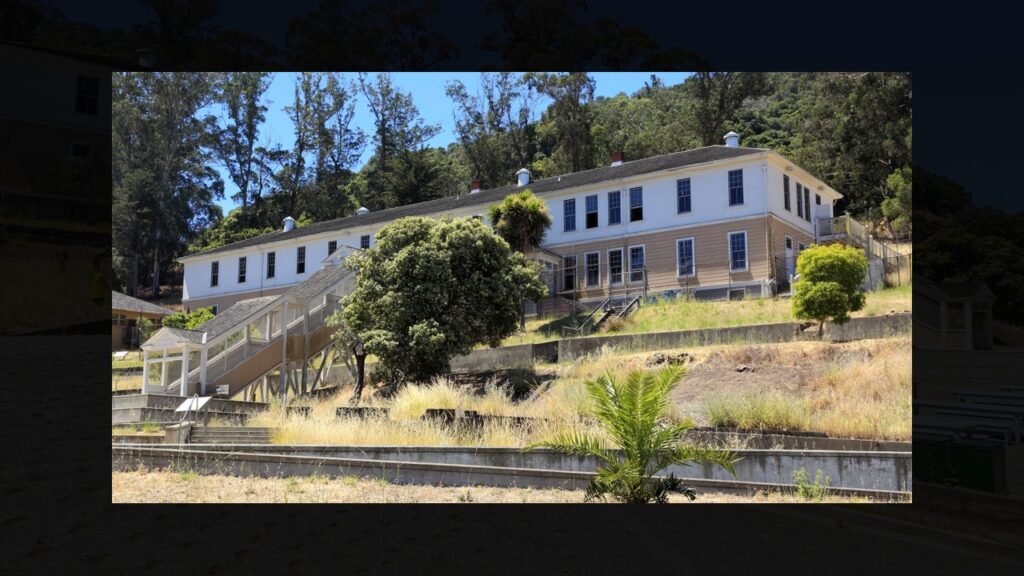

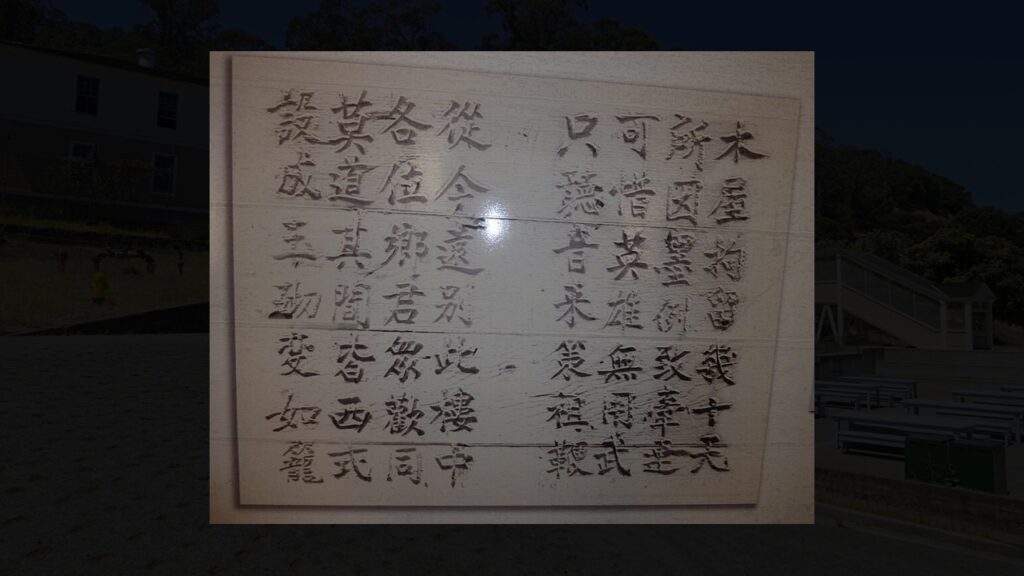

This Bay Area island’s most dangerous contraband wasn’t weapons – it was poetry

-

Kansas7 days ago

Kansas7 days agoThis Arkansas mob attacked children. Then the 101st Airborne arrived.

-

West Virginia6 days ago

West Virginia6 days agoThis Confederate retreat birthed a new state—and Virginia never recovered

-

Alabama6 days ago

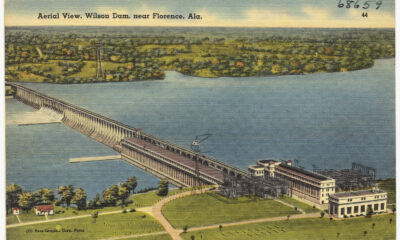

Alabama6 days agoBefore Las Vegas and Los Alamos, Alabama had America’s first instant mega-city

-

Idaho6 days ago

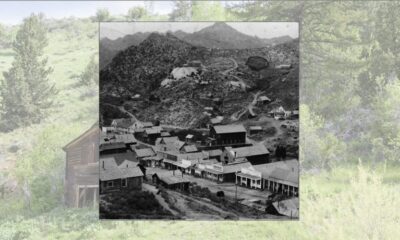

Idaho6 days agoMeet the 85-year-old who refused to let his Idaho town die. He stayed alone for 28 years.

-

Illinois2 days ago

Illinois2 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Illinois Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

-

Alabama5 days ago

Alabama5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Alabama Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

-

Kentucky7 days ago

Kentucky7 days agoThe governor who walked to his own assassination at Kentucky’s capitol in 1900

-

West Virginia6 days ago

West Virginia6 days agoThis West Virginia railroad was so steep, trains barely made it. Then came the fires.