California

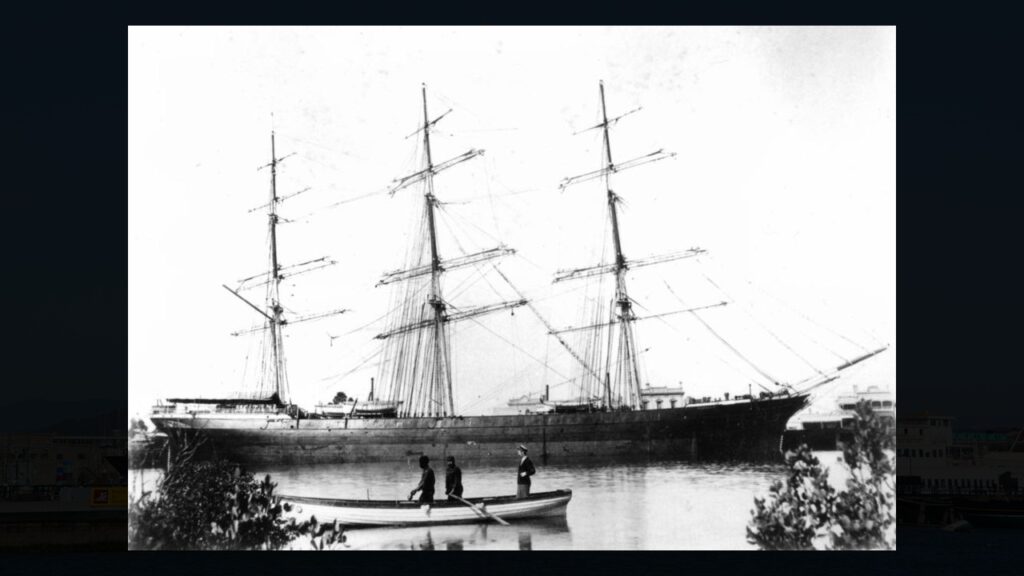

This restored square-rigger in San Francisco was actually a 19th-century human trafficking vessel

Published

5 minutes agoon

The Star Fleet’s Deadly Multi-Ethnic Labor Voyages

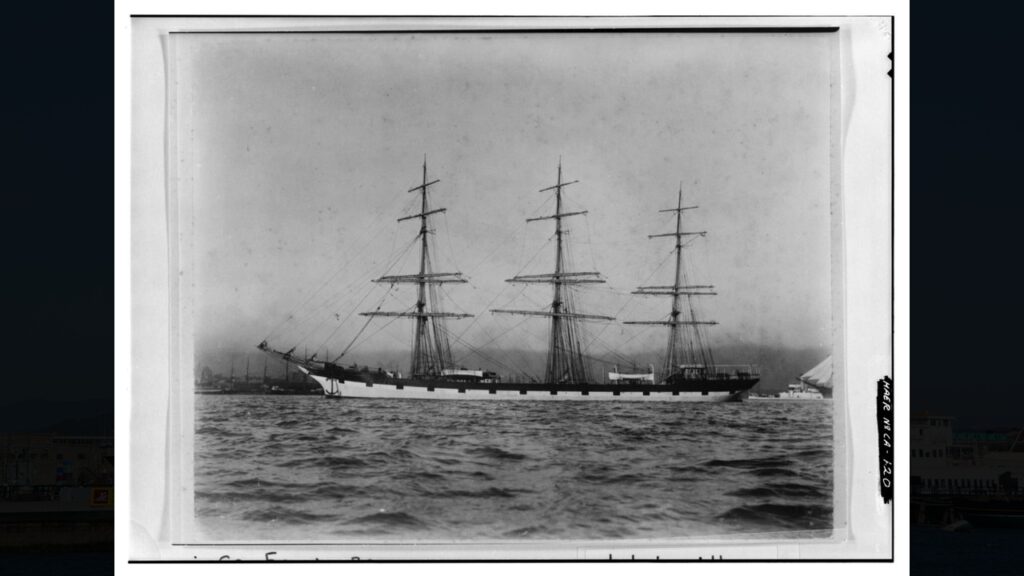

The Star Fleet ships of Alaska once linked two worlds.

From 1902 to 1930, these massive square-riggers made brutal 2,400-mile trips between San Francisco and remote Alaskan canneries.

On board, thousands of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Native Alaskan, Mexican, Black, and European workers lived in tight quarters for weeks. Yet below deck, harsh truths lurked.

The “China Gang” faced strict segregation, while Filipino “Alaskeros” dealt with cruel contractors who often left them stranded.

In 1908, this danger turned deadly when the Star of Bengal sank, killing 110 workers—mostly Asian laborers trapped below while white crew fled.

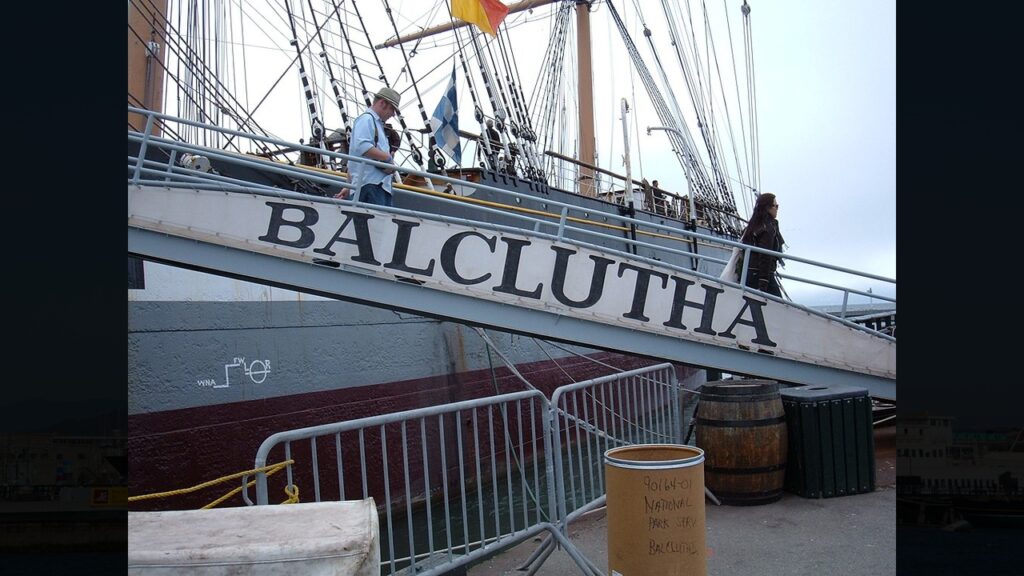

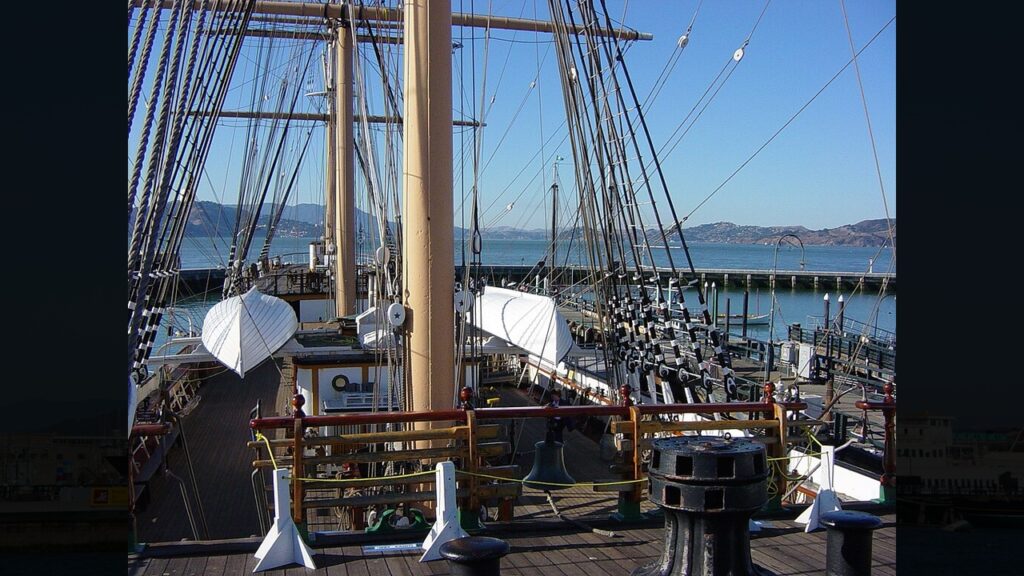

The Balclutha ship in San Francisco now stands as a rare witness to this forgotten chapter of American labor history.

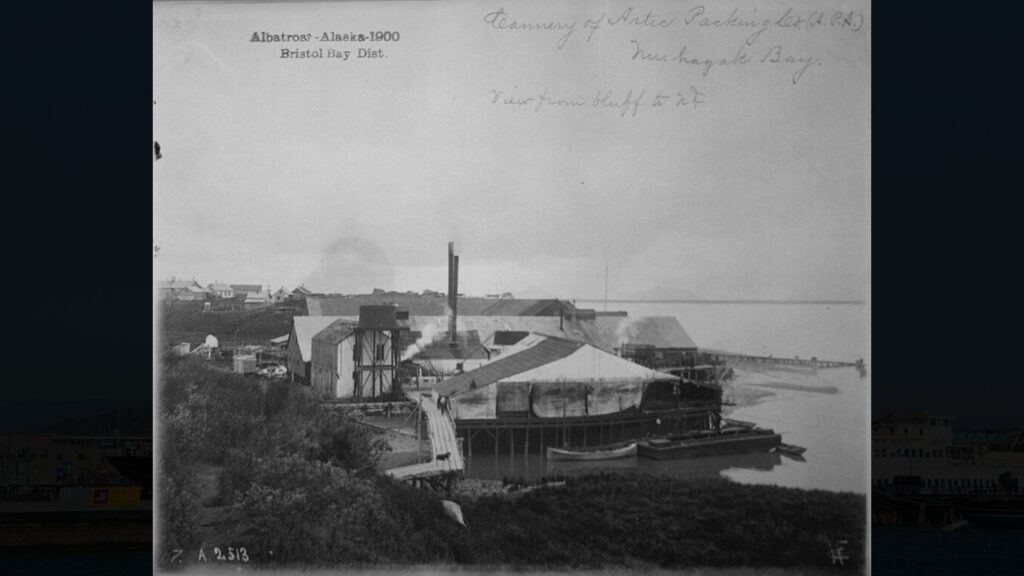

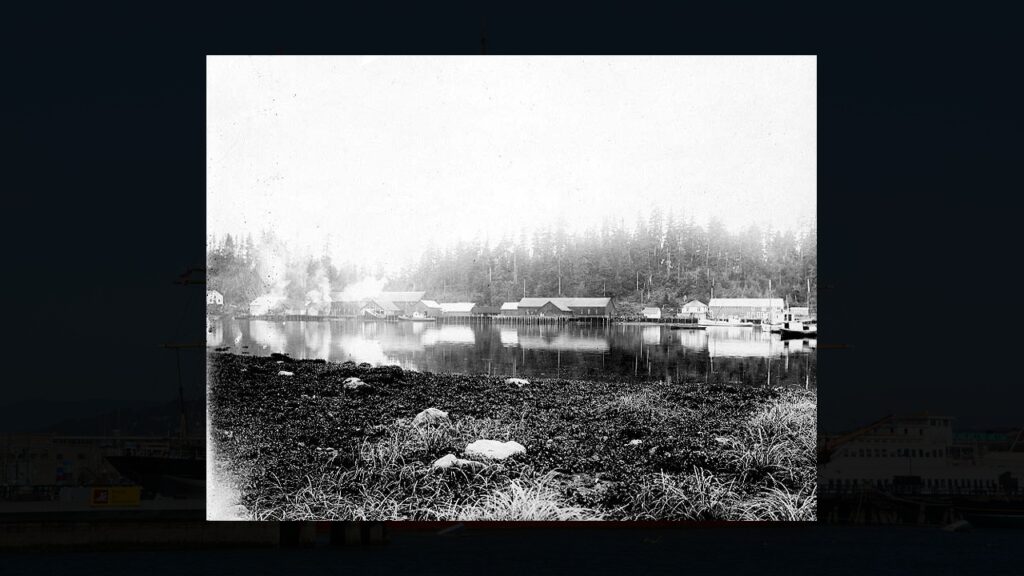

Big Business Took Over the Salmon Industry

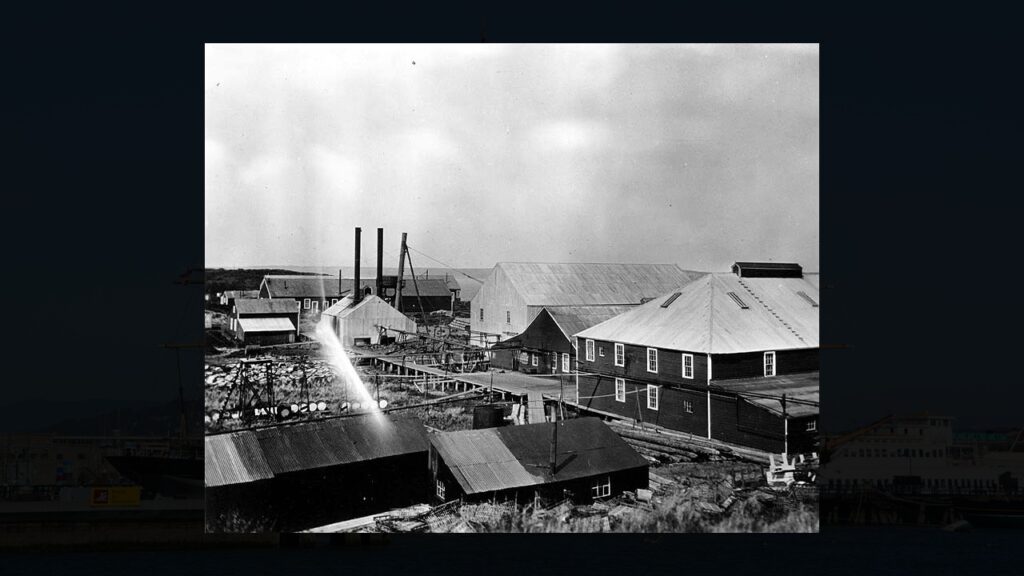

The Alaska Packers Association formed between 1891-1893 by joining 31 canneries to control salmon prices. Henry Frederick Fortmann ran the company until 1922.

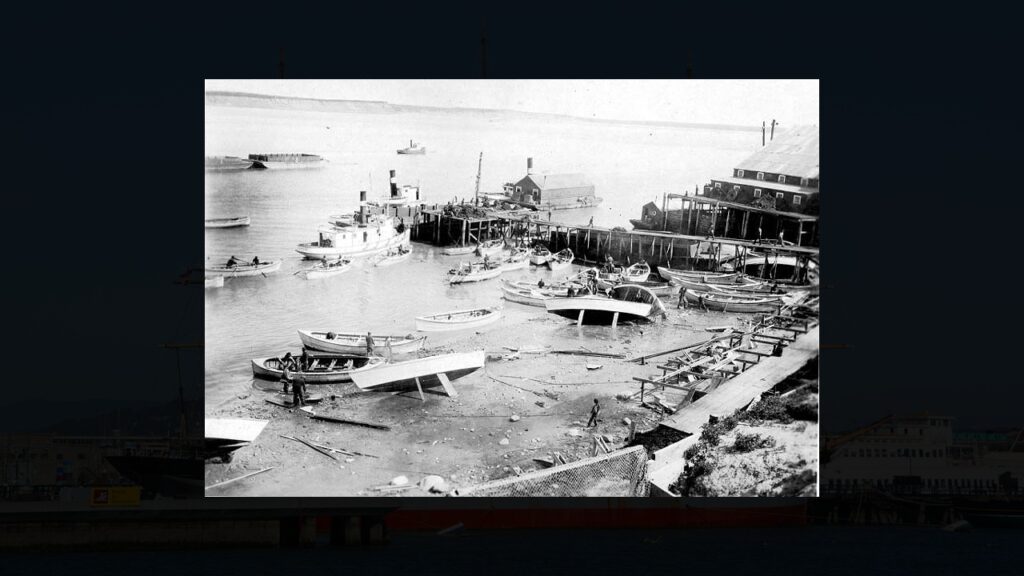

The company sent up to 30 square-rigged ships in its “Star Fleet” between San Francisco and Alaska each season. These huge sailing ships carried workers to canneries from Bristol Bay to Southeast Alaska.

The company built a special harbor in Alameda, California, called Fortman Basin, where the sailing fleet stayed during winter months.

Chinese Workers Made the Canneries Run

The Hume brothers hired 15 Chinese workers for their Columbia River canneries around 1872. Within two years, Chinese workers made up 95% of cannery workers, with the “China Gang” handling most processing work.

Cannery owners first brought Chinese workers to Alaska in 1878 for Klawock and Sitka canneries. Chinese labor contractors gave food, housing, and even whiskey and opium to workers.

Ships kept Chinese workers apart from white crew members during the long trips.

Three Weeks at Sea Tested Everyone’s Limits

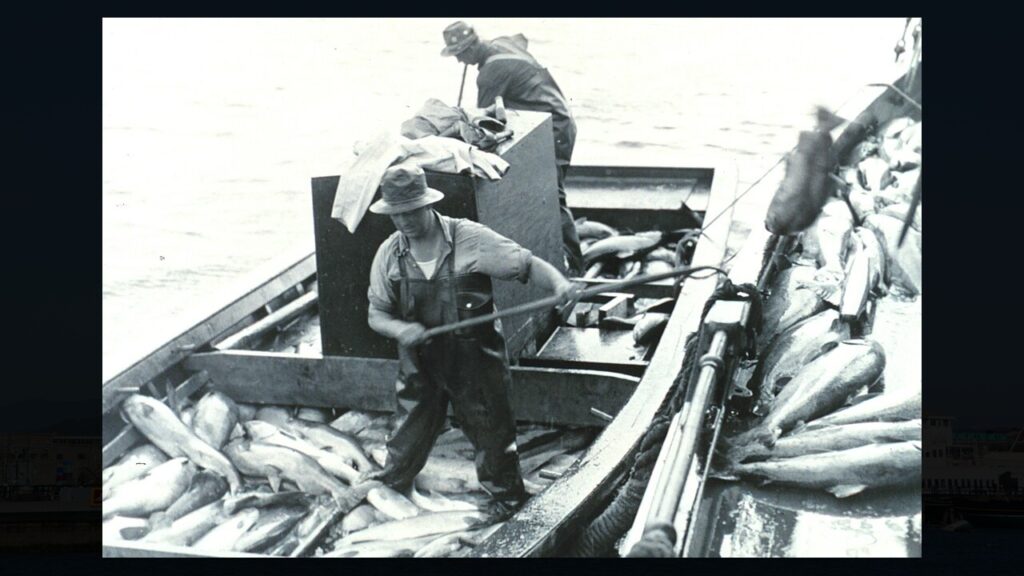

The spring trip from San Francisco to Alaska covered about 2,400 miles and took around three weeks. Each ship carried up to 300 men packed together, including fishermen, cannery workers, and crew members.

Workers slept in cramped cargo holds with extra wooden structures built to fit more laborers. Many ships lacked proper supplies and clean conditions, which some workers compared to human trafficking.

At season’s end, ships returned with up to 85,000 cases of salmon worth $500,000 in 1906 money.

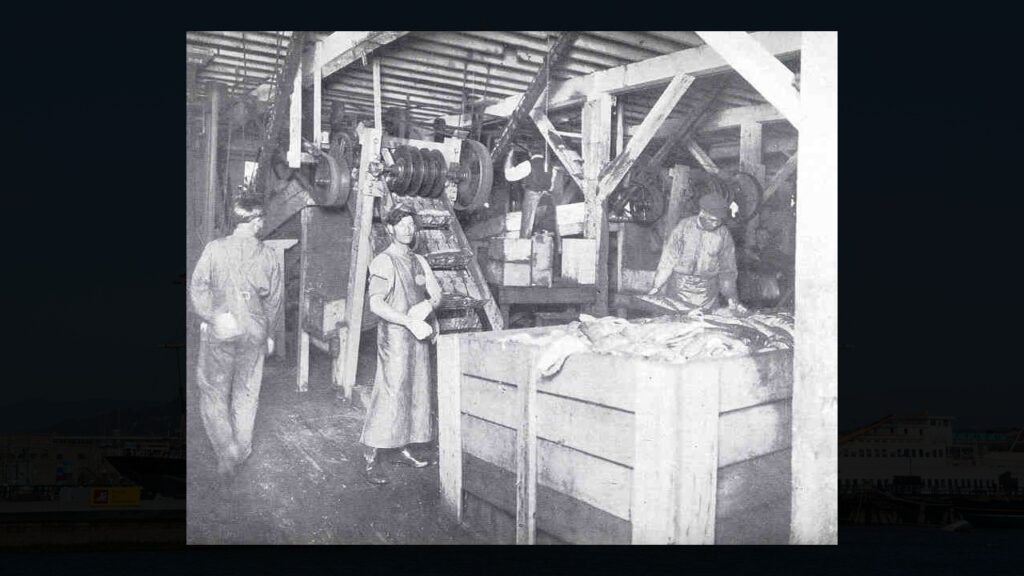

Cannery Life Meant Backbreaking Work

Workers processed up to 2,000 fish daily using long, thin knives that needed great skill and speed. The cannery floor stayed wet and noisy, with workers wearing raincoats and boots during shifts.

Chinese laborers worked more than 10 hours daily with no days off during peak salmon season. Company housing split workers by race, with Asian laborers getting the worst rooms.

These remote cannery sites worked like small villages with their own sleeping areas, dining halls, shops, and places to lock up troublemakers.

Labor Contractors Got Rich While Workers Suffered

Labor contractors charged workers for food, supplies, bedding and lodging that should have been free. Some contractors even left workers without pay when the season ended, stranding them in Alaska.

The dangerous work caused broken ribs, hand injuries, and fish poisoning, with 2-3 fishermen dying each year. Workers created underground trading with Alaska Natives to get better food than what the company gave.

From 1908-1941, company records tracked workers who spoke up about working conditions, noting when they got detained or fined.

Hundreds Drowned When the Star of Bengal Sank

The Star of Bengal sank near Coronation Island during a storm on September 20, 1908, while tugs Kayak and Hattie Gage pulled it.

The ship carried 138 people: 32 crew members and 106 cannery workers, mostly Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino men. The disaster killed 110 people, almost all Asian cannery workers trapped in the forward hold.

Only 15 of 36 white crew members died compared to 95 of 96 Asian workers.

Survivors told stories of panic and poor leadership during the escape, with claims that tugboat captains left the ship.

Filipino “Alaskeros” Became the New Workforce

After laws limited Chinese and Japanese immigration, canneries turned to Filipino workers to fill jobs. Nearly 1,000 Filipinos got hired by Chinese and Japanese contractors in 1921 for Alaska’s fisheries.

By the mid-1930s, Filipinos became the largest group in canneries, working as seasonal “Alaskeros. ” Travel conditions stayed terrible, with over 200 workers stuffed into vessels meant for 150 people.

Seattle’s International District became home for Alaskeros during the off-season months when they couldn’t work in Alaska.

People from Around the World Worked Side by Side

The workforce included Native Alaskan, Chinese, Mexican, Filipino, African American, and European immigrant workers.

Native Alaskan families often worked together during fishing season before going back to their villages. Italian fishermen caught salmon while Asian workers processed and canned the fish.

Workers shared meals with foods from their cultures: pancit, chicken adobo, salmon, frybread, and pozole.

Cultural mixing led to marriages between different groups, particularly between Filipino men and Alaska Native Lingít women.

Workers Fought Back Against Terrible Conditions

The Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union started on June 19, 1933, in Seattle as the first Filipino-led union in America.

Tragedy hit when union president Virgil Duyungan and secretary Aurelio Simon were killed on December 1, 1936, by a labor contractor’s nephew.

In 1937, the union joined the larger United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse, and Allied Workers of America.

Workers won their fight against the contract labor system, getting better pay, hours, and cleaner working conditions. The group later became Local 37 of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen Union by 1950.

Steam Power Ended the Era of Sailing Ships

Steam-powered boats gradually replaced sailing ships by the 1920s, though Alaska Packers Association still owned 14 square-rigged ships in 1927.

After salmon production dropped, Del Monte Corporation bought the company in 1982. Machines and changing immigration laws cut the need for seasonal migrant workers.

Filipino and Alaska Native workers filed a discrimination lawsuit against Wards Cove Packing Company in 1982. The old cannery village system changed into modern processing facilities with better working conditions.

The Last Traces of the Star Fleet Still Float Today

Only two Star Fleet ships remain: Star of India in San Diego and Balclutha (formerly Star of Alaska) in San Francisco.

The multi-ethnic workforce helped make Alaska the world’s largest salmon producer despite facing constant segregation and exploitation.

The contributions of Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, and other immigrant workers rarely appear in history books.

The Star of Bengal wreck site got nominated for the National Register of Historic Places to honor the Asian cannery workers who died there.

Fortman Basin in Alameda changed from an industrial harbor to a modern marina, showing how the industry transformed over time.

Visiting Balclutha (Square-Rigger), California

The Balclutha is temporarily at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo at 560 Nimitz Avenue while Hyde Street Pier gets renovated. You can view the ship from the Mare Island seawall, though boarding might be limited.

The usual $15 entrance fee is suspended, so access is free. Other historic ships like C.A. Thayer and Eppleton Hall are moored nearby.

The site includes pre-Civil War shipyard buildings as part of the National Historic Landmark.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

John Ghost is a professional writer and SEO director. He graduated from Arizona State University with a BA in English (Writing, Rhetorics, and Literacies). As he prepares for graduate school to become an English professor, he writes weird fiction, plays his guitars, and enjoys spending time with his wife and daughters. He lives in the Valley of the Sun. Learn more about John on Muck Rack.

This restored square-rigger in San Francisco was actually a 19th-century human trafficking vessel

Walk the Seven Hollows trail where one doctor’s eavesdropping saved Arkansas forests

The forgotten Alaska connection to Seattle’s groundbreaking 3.7 million visitor World’s Fair

The moment America officially fractured in two is remembered at this Alabama star

Meet the blind teacher who defied politicians and built West Virginia’s first disability school in Romney

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania3 days ago

Pennsylvania3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina4 days ago

North Carolina4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Nebraska6 days ago

Nebraska6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Nebraska Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York4 days ago

New York4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina2 days ago

South Carolina2 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio4 days ago

Ohio4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia5 days ago

Georgia5 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story