Colorado

This Colorado mining town still echoes with an Irish miner’s defiant words from 10,200 feet

Published

20 hours agoon

By

Leo Heit

Michael Mooney’s Failed Strike Against Leadville’s Silver Kings

In 1880, Irish miner Michael Mooney stood up to the silver kings of Leadville, Colorado. When the Chrysolite Mine tried to dock pay and ban talking during shifts, Mooney led 2,000 miners to walk out.

These men, many who had fled Ireland’s famine, wanted fair pay and safer work in the dangerous mines. For three weeks, they held firm with peaceful marches through town.

Then the governor sent in troops. The strike failed, but the story lives on.

Today, Leadville Historic District preserves this battle between working men and mining giants where you can walk the same streets as Mooney and his brave miners.

Irish Miners Left Starving Ireland for Colorado’s Silver Rush

By 1880, Irish folks made up nearly one in four miners in Leadville’s silver district, making them the biggest group of newcomers there.

Most ran from Ireland’s Great Hunger and tough British rule, hoping for better lives in America’s silver towns.

About 3,000 Irish people lived in Leadville, forming the largest Irish group in the western US outside California.

These miners worked dangerous underground jobs for just $2-3 a day while living in simple shacks on Leadville’s east side.

The harsh mountain air and lung sickness killed many Irish, with most dying shockingly young at 23.

Big Companies Took Over Leadville’s Silver Mines

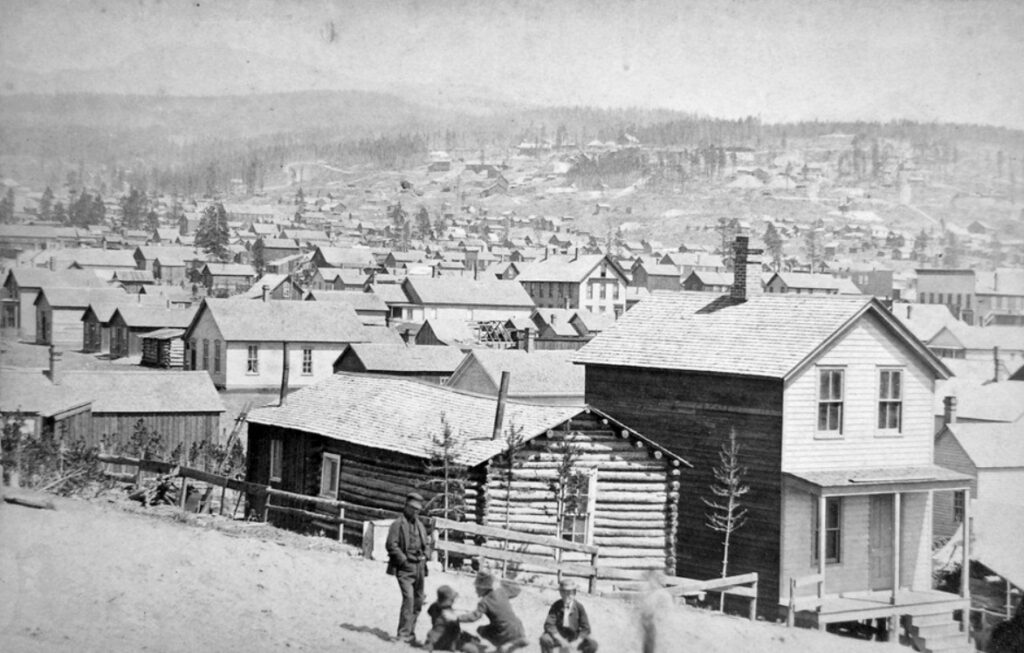

Leadville boomed in 1879 with 30,000 people, making it Colorado’s second-biggest city then.

By 1880, just eleven companies ran over 80% of silver mining, ending the days when regular miners could own parts of mines.

Famous mines like Little Pittsburg and Chrysolite started running out of silver while their stocks were being played with.

Company owners replaced the understanding miner-owners who knew the real dangers workers faced every day.

This takeover meant miners lost their direct link to mine owners and faced stricter working rules as profits became more important.

Knights of Labor Helped Miners Fight Tough Conditions

Miners started the Miners’ Cooperative Union in January 1879 to stand up against dangerous conditions and low pay across the district. The local group joined the Knights of Labor as Local No.

1005, linking them to worker support across America.

Miners died at rates of six per thousand yearly, a number likely lower than reality since it counted safer jobs too. Union membership grew as mine owners added new rules and safety problems got worse.

This group gave miners the structure they needed to act together when things finally got too bad in spring 1880.

The Chrysolite Company Made Life Harder for Miners

The company tried taking $1 monthly from workers’ pay for forced medical insurance in early 1880. Bosses banned talking and smoking during work, claiming safety reasons but really just cutting workers’ freedom.

The last straw came when the company fired several underground bosses, saying they let miners work too slowly. These changes happened while Chrysolite faced money troubles from poor management choices.

Night workers on May 26 blocked day workers from entering the mine, starting what grew into a district-wide walkout.

Michael Mooney Led When Miners Needed Someone Brave

Dublin-born Michael Mooney, 28, was picked by fellow miners to lead the walkout from the Chrysolite mine.

Strikers marched from Chrysolite to Little Chief mine with Mooney up front, ready to tell management what they wanted. Over 2,000 miners stopped working by day’s end, shutting down mining across the district.

Mooney kept things peaceful to keep community support during the strike.

The miners wanted $4 daily pay instead of $3, eight-hour workdays, the right to pick their own shift bosses, and for the company to recognize their union.

The Words That Brought Thousands of Striking Miners Together

Mooney told his fellow miners about the dangerous work and health risks they faced daily underground.

His strong words spread through the mining camps: “Here we are today in a high altitude and living in the mines, breathing in the bad and stifling gasses, with every danger of hurting our health and losing our lives.”

He added firmly, “Now we have just come to this conclusion, that if they can pull the reins, we can pull tighter and we are determined to have our rights no matter what comes.”

Mooney knew how public opinion mattered for Irish newcomers who already faced unfair treatment in America.

Mine Owners Refused to Give In to Any Demands

Manager George Daly at Little Chief told strikers he needed to ask eastern owners before agreeing to pay more.

All mine managers across the district turned down the $4 daily wage and eight-hour day demands without really thinking about them. Owners hired armed guards to protect mines and scare strikers away.

Talks between workers and management completely failed with no middle ground offered by the companies.

The strike went on as miners stayed united across the district for nearly three weeks despite growing pressure from owners.

Thousands Walked Silently Through Town in Protest

On June 12, 1880, hundreds of strikers walked quietly through Leadville’s streets in a show of unity that impressed even those against them.

Five thousand miners moved in a single line from south to north down Main Street without saying a word. The march showed their discipline while avoiding fights with local police.

Law officers kept their distance, likely knowing they were greatly outnumbered by the peaceful protesters. This silent walk was a calm but powerful display of worker unity that caught everyone’s attention in town.

Business Leaders Asked the Governor to Send Troops

Mine owners and business leaders formed a citizens’ group on June 11 to break the strike by any means needed.

The group said they would create their own armed force to protect any miners willing to work for the old wages.

They asked Governor Frederick Pitkin to send weapons and bullets to support their fight against the strikers.

The group complained the sheriff had sided with strikers and could no longer protect their property from possible damage.

Tension grew as both sides gathered supporters for what looked like a coming fight in Leadville’s streets.

Governor Pitkin Crushed the Strike With Military Force

After brief hesitation, Governor Pitkin gave in to property owners and declared martial law on June 13, sending in state troops.

Major General David Cook arrived June 14 with sixteen companies of volunteer state militia ready to enforce the governor’s orders.

These military forces clearly backed mine owners against the striking workers from the moment they arrived in town.

Armed state intervention took away the miners’ main leverage: their ability to stop production through their strike. Mooney faced threats of lynching from angry vigilantes and went into hiding to save his life.

The Miners’ Fight Ended Without a Single Victory

Most mines resumed work on June 15 without any wage increases or improvements to working conditions.

A mass meeting on June 17 made it official that miners would return to work under the same pre-strike conditions they had fought to change.

The union fell apart shortly after the failed strike, with many leaders leaving town either by choice or forced out by threats.

Mooney left Leadville and eventually died in Los Angeles at age 72, his brave labor leadership largely forgotten by history.

The strike’s failure marked Leadville’s shift from wild boomtown to stable city with firmly established power relationships that favored owners over workers.

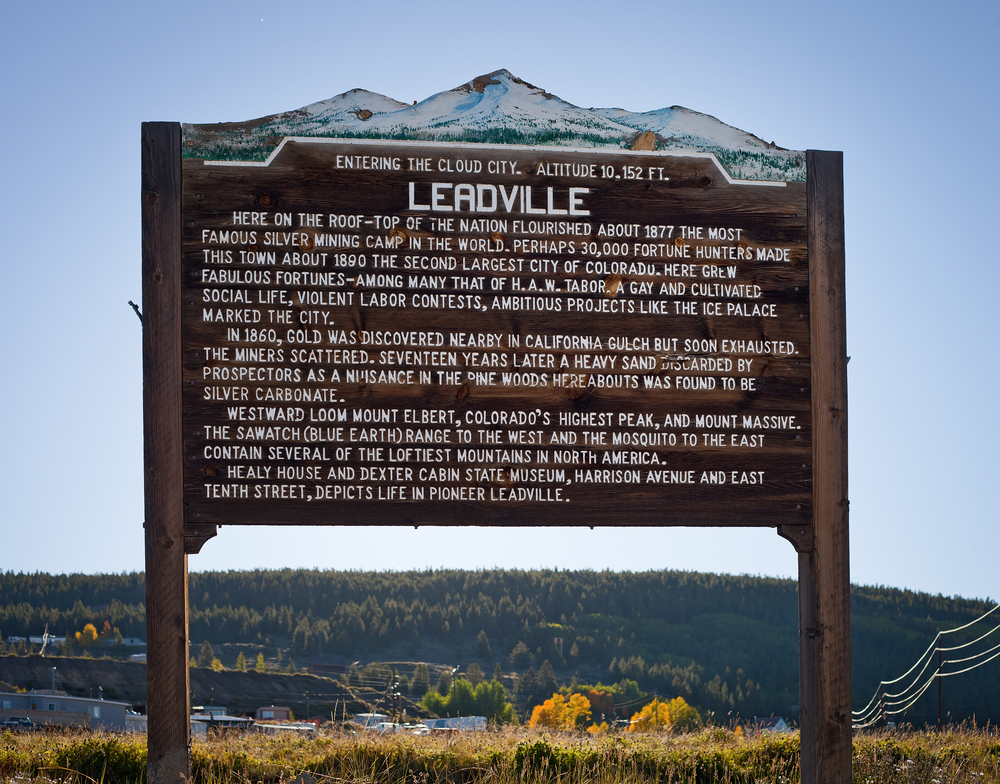

Visiting Leadville Historic District, Colorado

You can learn about Michael Mooney and the 1880 miners’ strike at several Leadville museums.

Start at the National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum on West 9th Street or the Healy House Museum on Harrison Avenue, which costs $10 for general admission or $3 for exhibits only.

Get a Museums of Leadville Passport to visit multiple historic sites, and use their self-guided walking tours with maps to explore where Irish miners fought for better wages before martial law ended their strike.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

Currently residing in Phoenix, Arizona with his wife and Pomeranian, Mochi. Leo is a lover of all things travel related outside and inside the United States. Leo has been to every continent and continues to push to reach his goals of visiting every country someday. Learn more about Leo on Muck Rack.

Test post 2

Test Post

15 mountain towns in America where fall feels like a painting

This Connecticut submarine museum boasts the Cold War’s most desperate shopping trip

This Colorado town was literally built to shame its sinful neighbor

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania4 days ago

Pennsylvania4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina5 days ago

North Carolina5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine6 days ago

Maine6 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York5 days ago

New York5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina3 days ago

South Carolina3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio5 days ago

Ohio5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia6 days ago

Georgia6 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story

New Hampshire6 days ago

New Hampshire6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New Hampshire Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else