Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

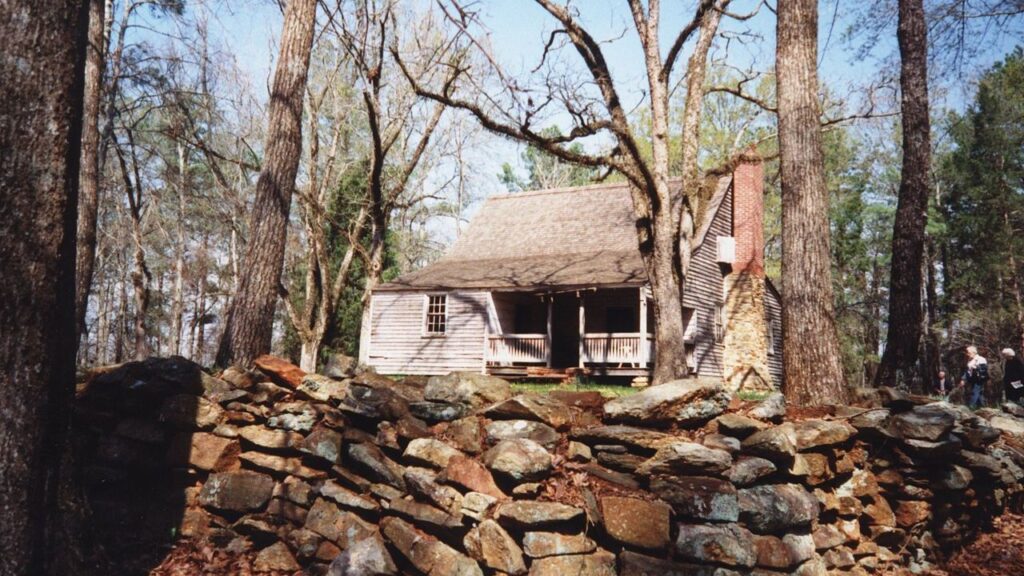

The Gradual Exodus from Jarrell’s Georgia Plantation

The Jarrell Plantation tells a story of freedom that took years to unfold. By 1863, John Jarrell owned 42 enslaved people who worked his 600-acre Georgia cotton farm.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, these newly freed men and women faced a tough choice. Many first stayed on as paid workers while Jarrell grew his farm to 766 acres.

Yet over time, they left one by one, seeking better lives elsewhere.

By Jarrell’s death in 1884, most had gone, leaving only stone ruins where their quarters once stood.

The Jarrell Plantation State Historic Site now marks this quiet exodus that showed how freedom meant, above all else, the right to walk away.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

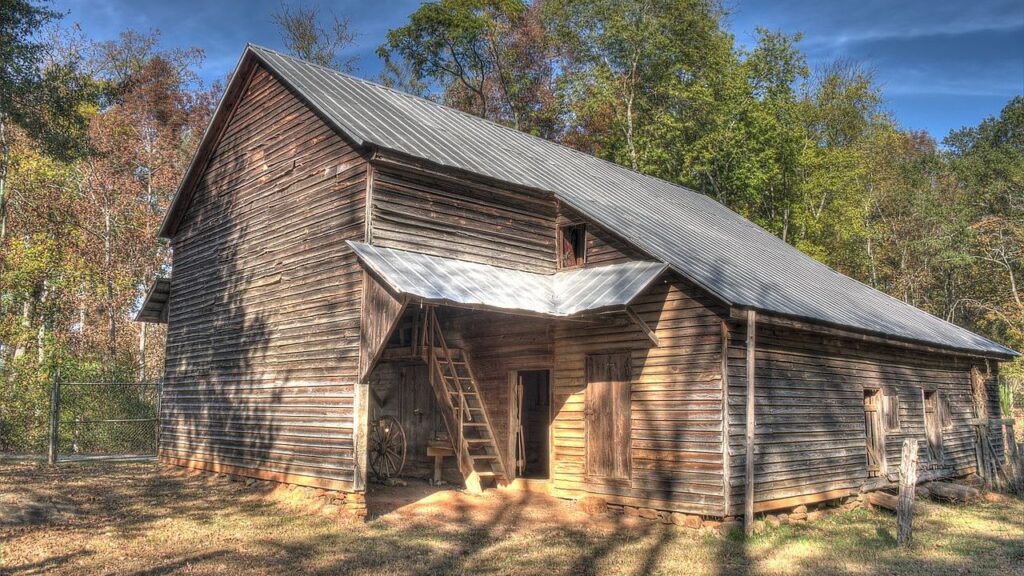

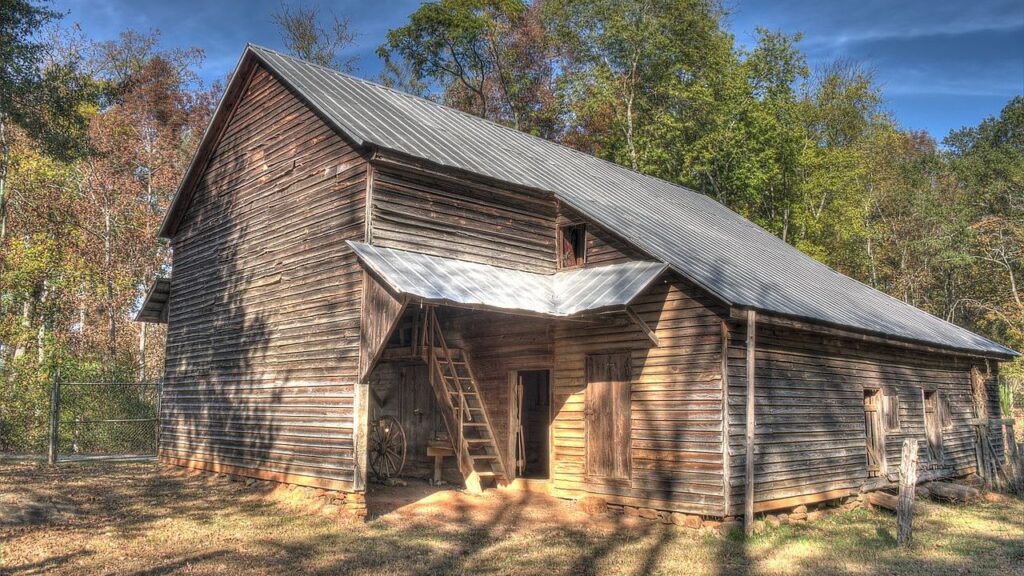

John Jarrell Built His Cotton Empire on Enslaved Labor

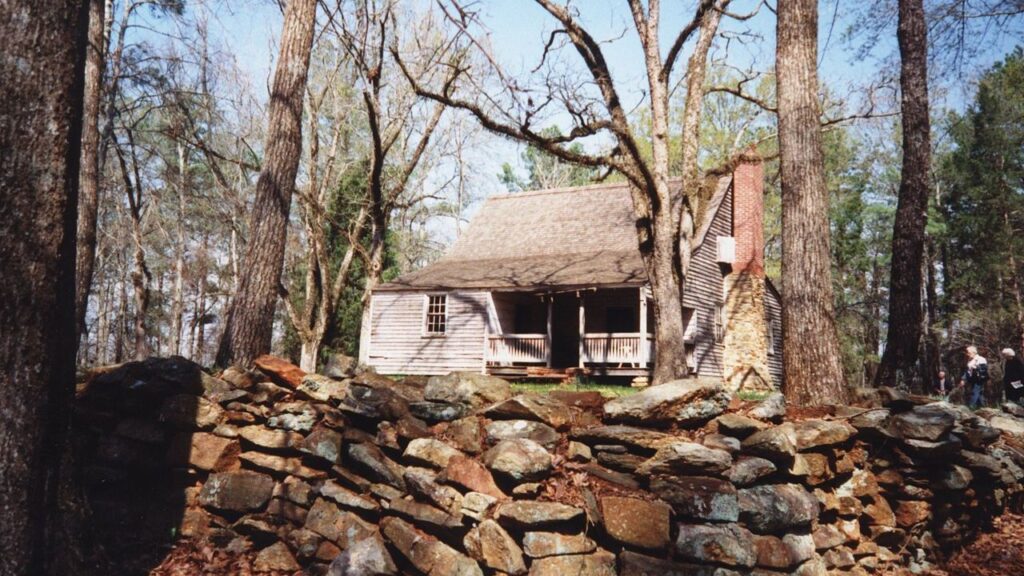

John Fitz Jarrell built his pine farmhouse in 1847 on red clay hills in Georgia. By 1860, Georgia grew two-thirds of the world’s cotton through farms like his.

The plantation grew from a small start to 600 acres by 1863, worked by 42 enslaved African Americans.

Jarrell ran what folks back then called a “middle-class” Southern plantation, making money from cotton picked by enslaved workers.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

Sherman’s Troops Turned the Plantation Upside Down

Sherman’s army raided the plantation during his March to the Sea in late 1864. They burned buildings and freed the enslaved workers.

The plantation also lived through typhoid fever outbreaks in the 1860s. Union soldiers broke up the plantation system that had run Georgia’s economy for years.

By 1865, the war ended plantation slavery across Georgia.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

Freedom Came Gradually to Georgia’s Plantations

Freedom reached Georgia’s 400,000+ enslaved people slowly throughout 1865. News of freedom spread from one group to another as enslaved people eagerly shared what they heard.

Many slave owners tried to keep the old system going until soldiers forced them to free their workers. Freedom brought uncertainty since no one knew what would replace slavery.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

Many Freed People Had No Choice But to Return

Most freed people at Jarrell and across Georgia first had few options but to go back to plantations by the late 1860s. They needed money and jobs on white-owned farms since they lacked resources to farm on their own.

Sherman’s Field Order No. 15 promised coastal land to some, but most freed people got nothing.

Without land reform, most lacked what they needed to farm for themselves.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

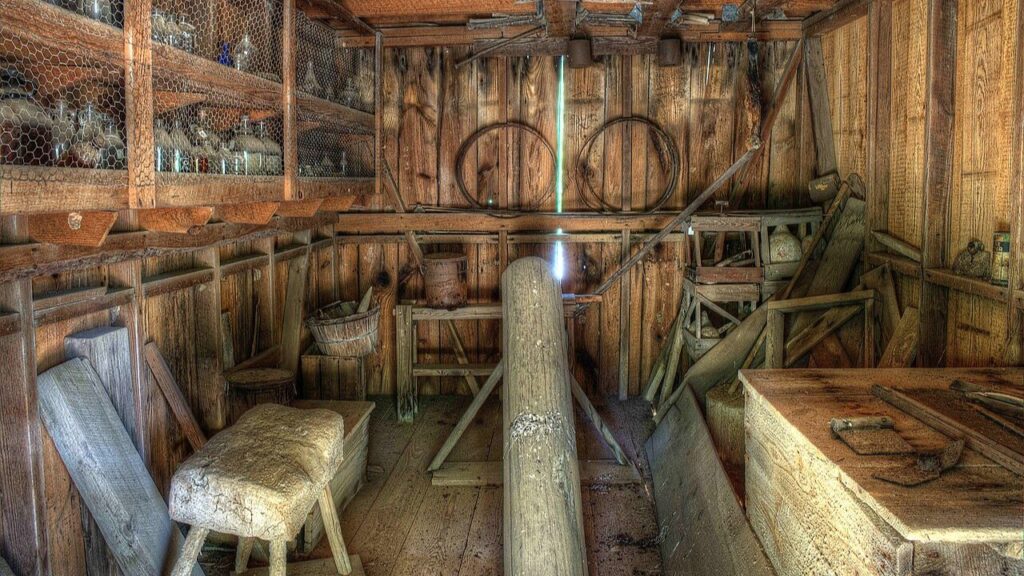

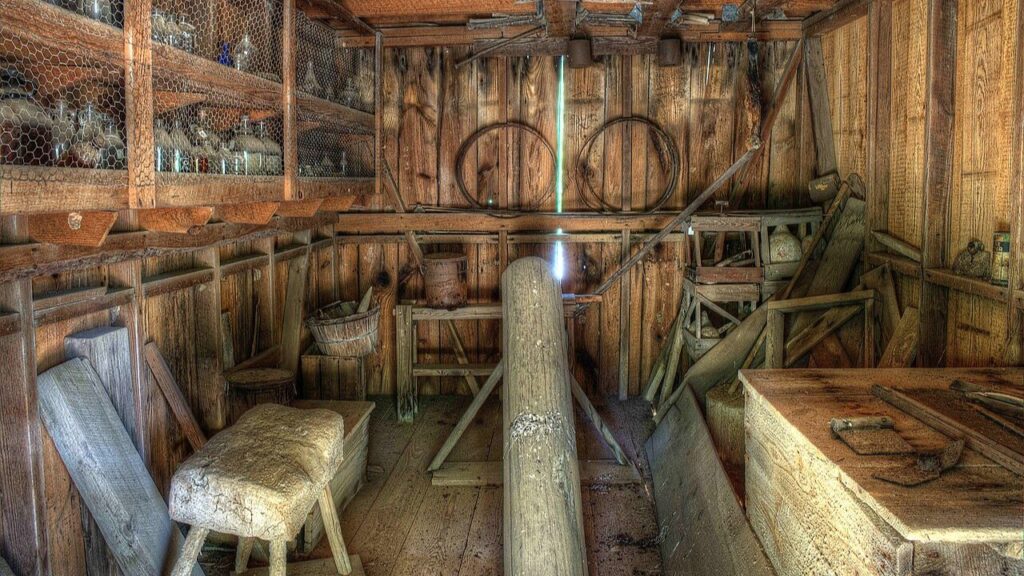

Working Arrangements Changed After Slavery Ended

John Jarrell kept farming after the war with help from formerly enslaved people, growing to nearly 766 acres. The Freedmen’s Bureau tried to set up fair work deals through a contract labor system.

Many freed people hated this system and refused to work under its rules. Sharecropping slowly replaced both wage labor and contract systems across the South.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

The Right to Move Became the First Real Freedom

Freed people used what historian Wesley Allen Riddle called their “most basic and symbolic” freedom: the ability to move. Ideally, freed people wanted to break ties with their former owners by getting their own land.

Some found brief periods of freedom or better work on other farms. Freedom meant they could leave when things got bad or better chances came along.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

Debt Trapped Many in a New Kind of Bondage

Sharecropping often trapped workers in debt cycles that looked much like the old plantation system. High interest and unfair contracts kept many sharecroppers tied to landowners.

The crop lien system let workers buy supplies on credit backed by future crops, creating more debt. Many found this “new freedom” still kept them poor, much like slavery did.

Wikimedia Commons/Andreas Hörstemeier

The Aging Plantation Owner Watched His Workforce Dwindle

As John Jarrell got older in the 1870s and early 1880s, work conditions on the farm likely got worse. The freed people started leaving during Jarrell’s final years as he lost his grip on running things.

Slave houses fell apart and disappeared during this time, showing he spent less on worker housing. People leaving matched what happened across Georgia after the Civil War.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

By 1884, Almost Everyone Had Left Jarrell Plantation

By the time John Jarrell died in 1884, most freed workers had left the plantation. The exit happened over nearly twenty years as workers used their freedom to move.

Some left to find family members sold during slavery, while others looked for better jobs. Only ruins remained where slave quarters once stood, marking the end of an era.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

People Voted With Their Feet Across the South

Jarrell’s story matched what happened to plantation owners across Georgia as they tried to keep their farms going.

Many freed people moved to nearby towns and cities or joined early waves of people heading North and West. Starting in the 1870s, at least 40,000 African Americans became “Exodusters,” moving to Kansas and nearby states.

This movement came before the massive Great Migration of the early 1900s.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

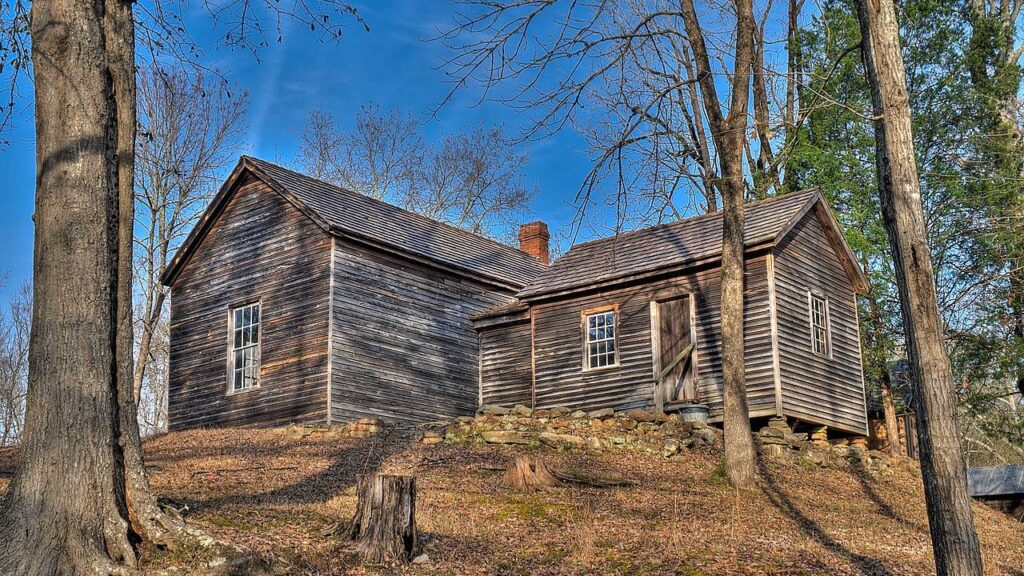

The Ruins Tell a Story of Resistance Through Departure

The ruins of slave quarters at Jarrell Plantation today stand as silent testimony to the workers who chose freedom over familiarity.

The gradual exodus challenged the assumptions of white landowners who expected freed people to remain in their old homes.

The departure represented a victory for human dignity, as workers refused to accept “freedom” that resembled slavery.

John Jarrell’s son Dick had to completely reorganize the farm’s operations, turning to mechanization and new industries after the workforce left.

Wikimedia Commons/Dsdugan

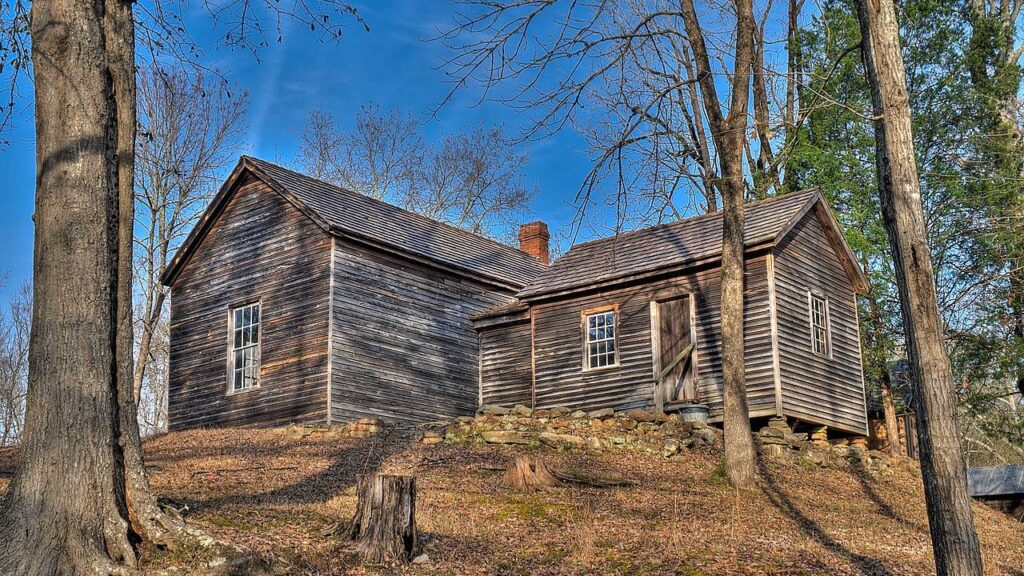

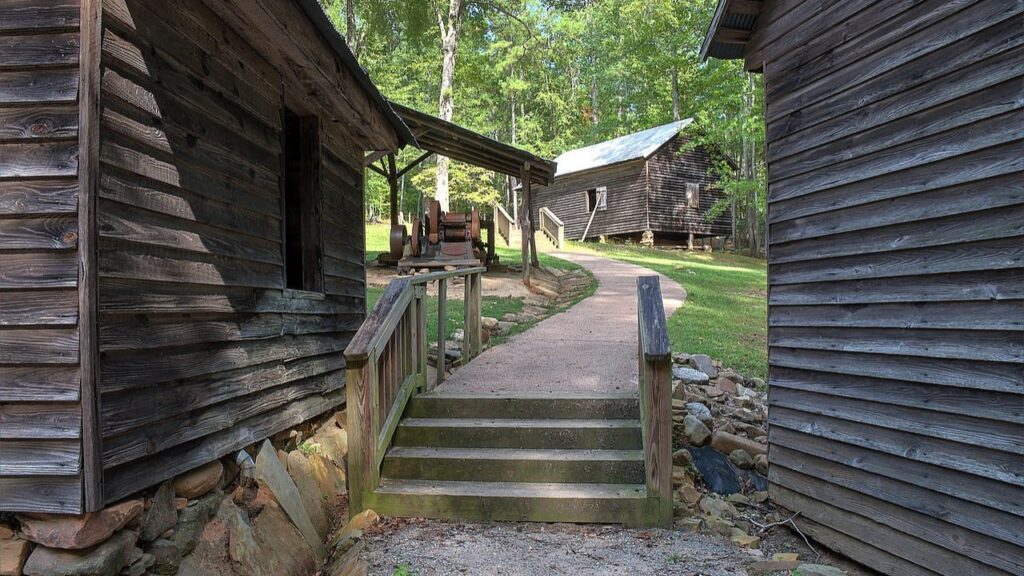

Visiting Jarrell Plantation State Historic Site, Georgia

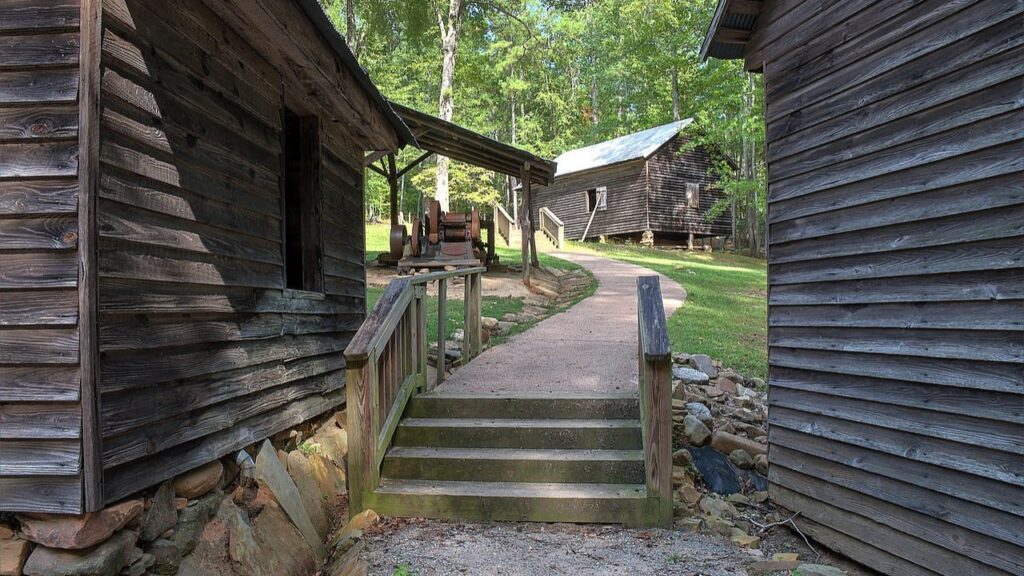

Jarrell Plantation at 711 Jarrell Plantation Road in Juliette shows you what happened after the Civil War when freed people left plantations.

You can see over 25 original buildings from the 1800s including the farmhouse, cotton gin, and sawmill. Adults pay $6.50, seniors $6. 00, and kids 6-17 pay $4.00.

The site is open Thursday through Sunday from 9am to 5pm.

Walk the half-mile trail to learn about this major change in Georgia’s history.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

Illinois4 days ago

Illinois4 days ago

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days ago

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days ago

Minnesota2 days ago

Minnesota2 days ago

Indiana4 days ago

Indiana4 days ago

Kentucky4 days ago

Kentucky4 days ago

Maryland3 days ago

Maryland3 days ago

Illinois4 days ago

Illinois4 days ago