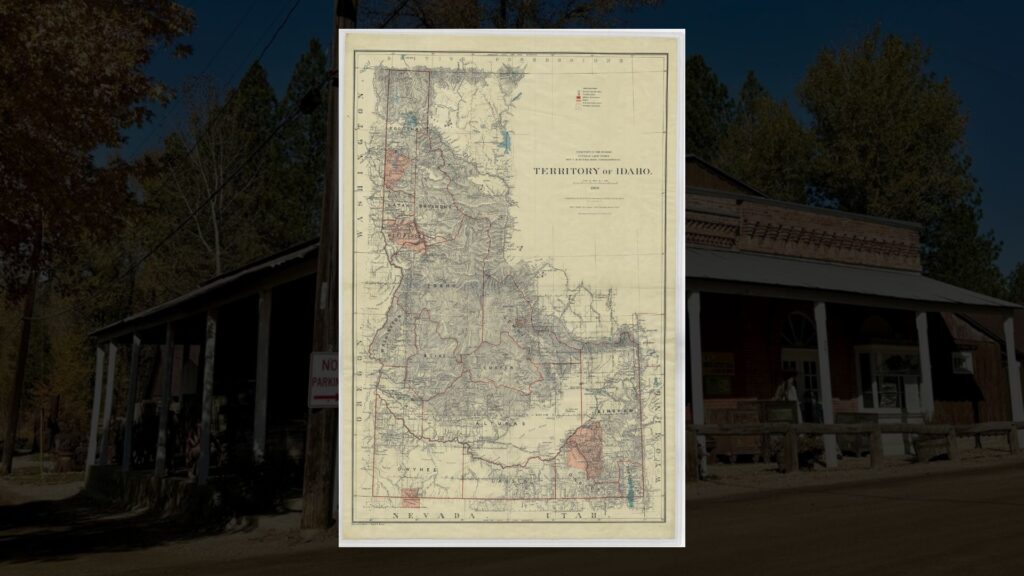

Idaho

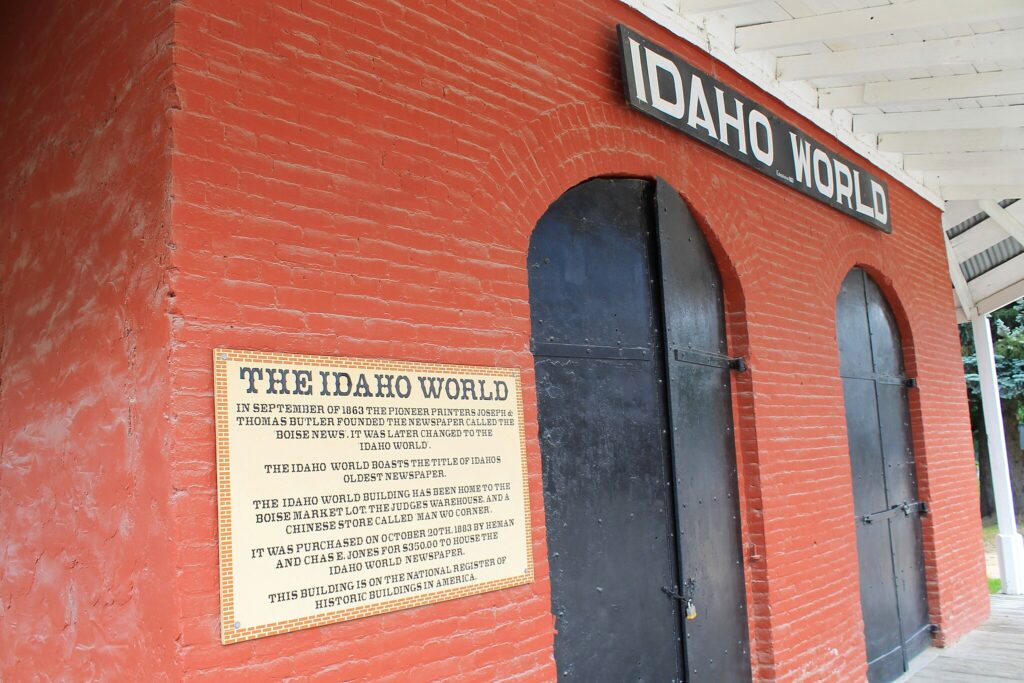

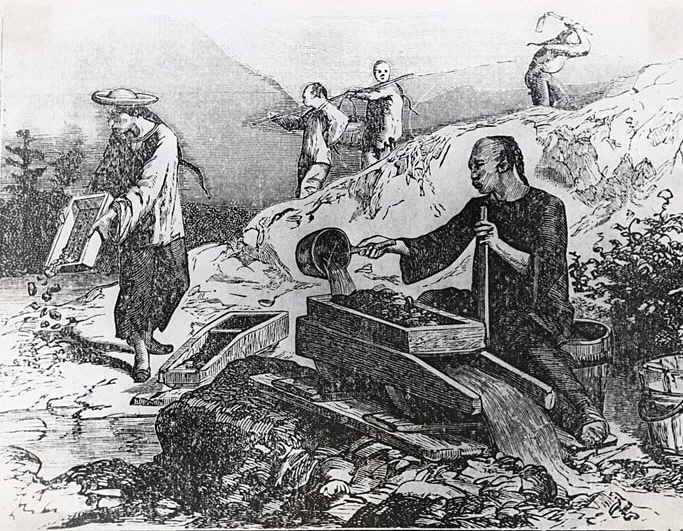

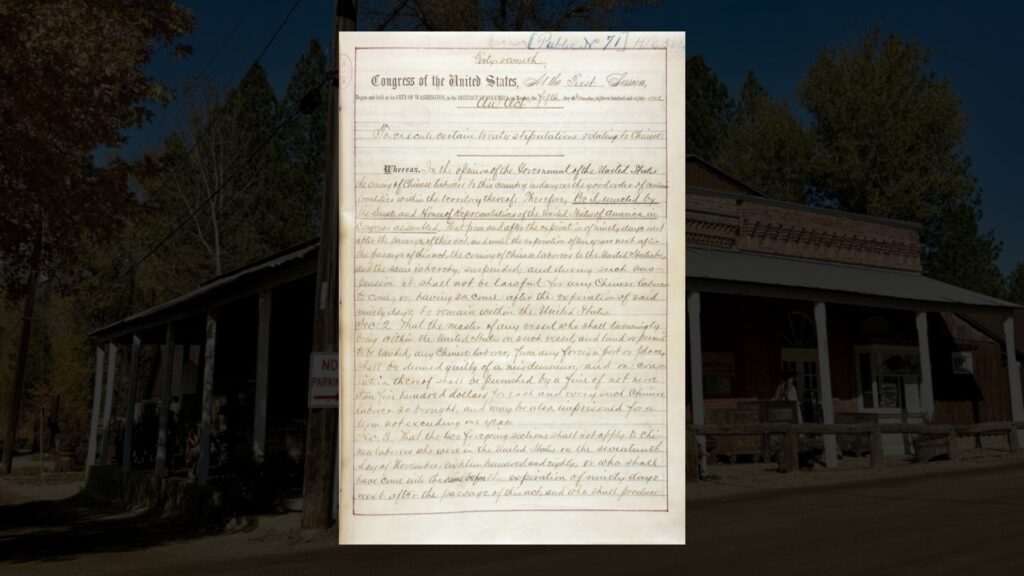

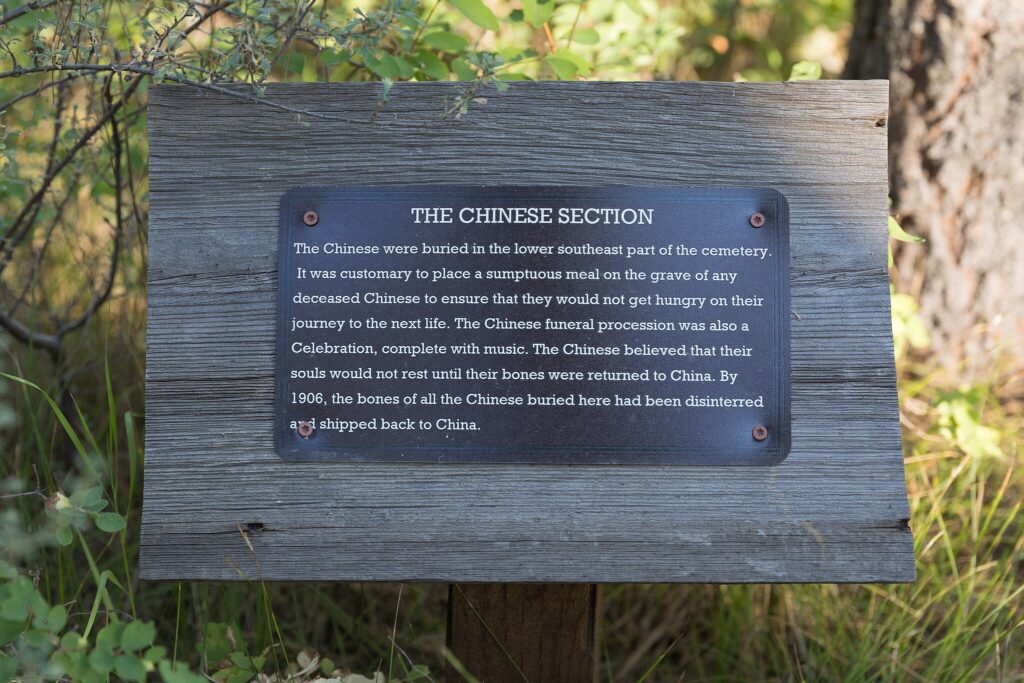

The Idaho gold rush city that could have been America’s first Chinatown

-

Florida6 days ago

Florida6 days ago12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

-

USA6 days ago

USA6 days agoBest national parks for a quiet September visit

-

New Hampshire6 days ago

New Hampshire6 days agoIn 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

-

New Mexico6 days ago

New Mexico6 days agoThe radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

-

USA5 days ago

USA5 days agoBest September biking routes for families

-

USA6 days ago

USA6 days agoBest September foodie destinations in the US

-

USA4 days ago

USA4 days agoTop September weekend getaways for couples

-

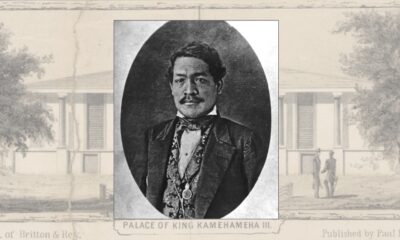

Hawaii5 days ago

Hawaii5 days agoHow Lahaina became the birthplace of Hawaii’s civil rights in 1840