Maryland

Harriet Tubman’s first Underground Railroad rescue: saving her own niece from a Maryland slave auction

Published

3 months agoon

By

Leo Heit

The 1850 Harriet Tubman’s First Rescue Mission

In December 1850, Harriet Tubman conducted her first rescue mission on the Underground Railroad.

She had escaped slavery herself just over a year earlier and was living in Philadelphia as a free woman, working as a domestic servant and cook.

Word reached her that her niece Kessiah Jolley Bowley and her two young children, James Alfred and Araminta, were scheduled to be sold at auction in Cambridge, Maryland.

The auction would separate the family forever, likely sending them to Deep South plantations where they would never see each other again.

This news compelled Tubman to risk her newfound freedom and return to the dangerous territory she had fled.

The Warning That Started Everything

Tubman received word from relatives and friends in Baltimore that Kessiah and her children would be auctioned at the Cambridge courthouse.

The Underground Railroad relied on networks of informants who passed along crucial information about pending slave sales through coded messages and trusted contacts.

Kessiah was owned by Eliza Ann Brodess, the same woman Tubman had escaped from two years earlier.

Brodess regularly sold slaves when she needed money, and had a reputation for breaking up families without hesitation. The connection ran deeper than ownership.

Kessiah’s mother Linah was Tubman’s sister who had been sold out of state in the 1830s, despite legal provisions for her freedom in Atthow Pattison’s will.

Planning The Rescue in Baltimore

Tubman traveled from Philadelphia to Baltimore, where her brother-in-law Tom Tubman hid her until the sale.

Baltimore had a large population of free blacks and was a crucial hub for Underground Railroad operations, with many safe houses and sympathetic contacts along the waterfront.

She worked with Kessiah’s husband John Bowley, a free black shipbuilder and blacksmith, to plan the rescue.

John had been manumitted by Levin Stewart sometime in the 1840s through a legal process where slaveholders formally freed enslaved people.

The plan they developed was risky but simple. John would attend the auction and bid on his own wife and children, then disappear with them before payment was due.

The Auction Day Deception

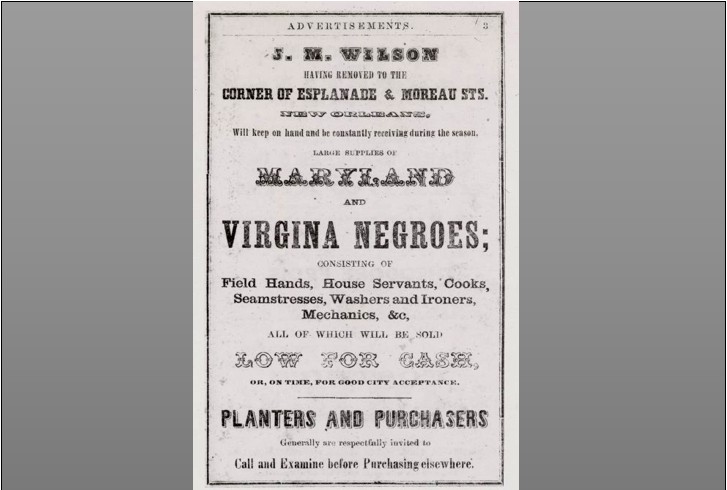

On the day of the auction, Kessiah and her two children stood before buyers at the Dorchester County courthouse.

Slave auctions were public events where enslaved people were examined like livestock, with buyers checking their teeth, muscles, and general health before bidding.

John Bowley made the winning bid for his wife and children, outbidding all other buyers. Free blacks sometimes purchased family members at auctions, so his presence wouldn’t raise suspicion among the white crowd.

When the auctioneer stepped away for lunch, John, Kessiah, and the children escaped to a nearby safe house. The lunch break timing was either fortunate or possibly arranged through bribery.

The Vanishing Act

When the auctioneer returned from lunch and called for payment, no one stepped forward. The winning bidder and his “purchases” had simply vanished, leaving confused officials and angry onlookers searching for answers.

Kessiah and her children were missing, having been secreted to a safe house within five minutes of the courthouse.

The Underground Railroad maintained a network of safe houses throughout the South, often in the homes of free blacks, sympathetic whites, or enslaved people willing to risk punishment.

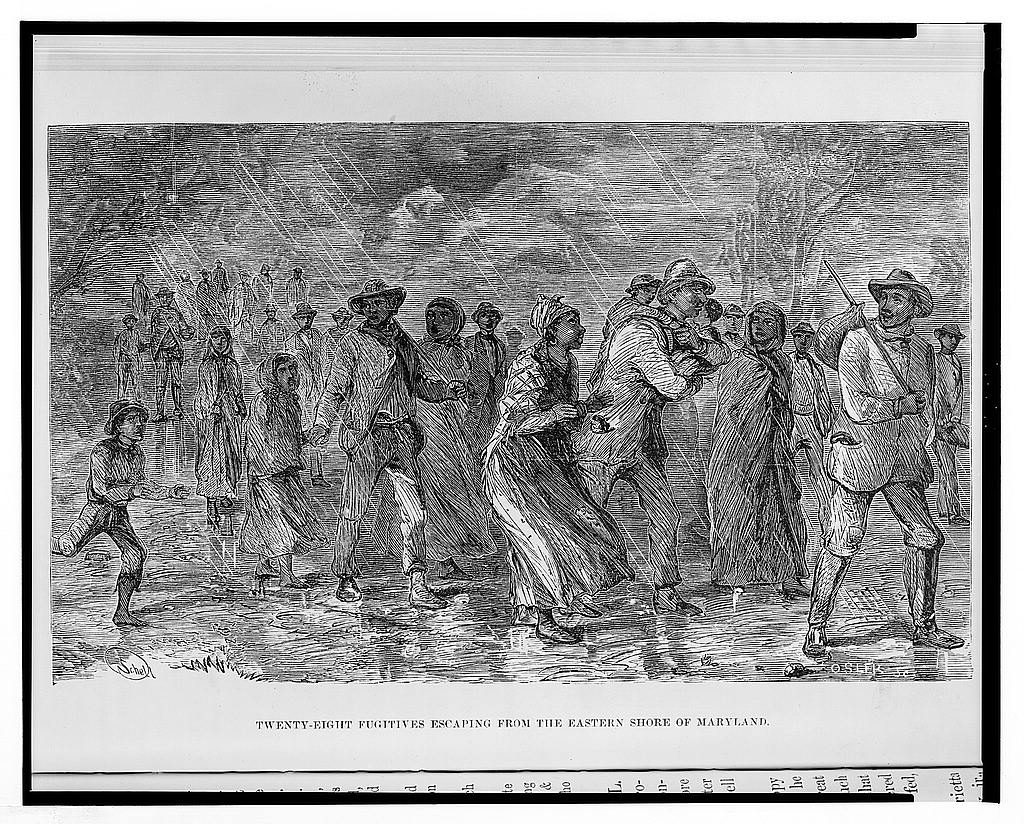

The Bowleys remained in hiding for several days before making their escape, waiting for the initial search efforts to die down and for the right conditions to attempt their dangerous journey.

The Dangerous Journey to Baltimore

When night fell, John Bowley sailed his family on a log canoe 60 miles from Cambridge to Baltimore.

A log canoe was a traditional Chesapeake Bay boat carved from a single large log, commonly used by watermen for fishing and transportation.

The December weather made the Chesapeake Bay crossing risky, with cold temperatures, unpredictable winds, and rough waters that could easily swamp a small boat.

Many attempted water escapes ended in drowning or capture. John was an experienced mariner who understood the bay’s currents, tides, and weather patterns.

His skills as a shipbuilder and blacksmith had given him extensive knowledge of boats and water travel, which proved essential for the family’s survival.

Reunion in Baltimore

Tubman met the Bowley family when they arrived in Baltimore after their boat journey.

She had been waiting anxiously, knowing that any delay could mean capture, punishment, or death for the escaping family.

She hid them for several days among friends and relatives in Baltimore’s waterfront community.

Baltimore’s Fell’s Point neighborhood had a large population of free blacks who worked as sailors, shipbuilders, and dock workers, providing natural cover for Underground Railroad operations.

The city’s maritime economy created opportunities for black workers while also providing convenient transportation routes for Underground Railroad conductors.

The hiding period allowed the family to rest, recover from their journey, and prepare for the next dangerous leg of their escape.

The Underground Railroad Network

Tubman used her connections with abolitionists and Underground Railroad agents to arrange the family’s journey.

The Underground Railroad was not an actual railroad but a secret network of people willing to help enslaved people escape to free states and Canada.

William Still, a prominent Philadelphia abolitionist known as the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” blessed Tubman’s mission to become a conductor.

Still kept detailed records of escaped slaves who passed through Philadelphia.

The network used railroad terminology as code: safe houses were “stations,” helpers were “conductors” or “stationmasters,” and escaping slaves were “passengers” or “cargo.”

This coded language helped protect the network from discovery by slaveholders and law enforcement.

Carrying on in Philadelphia

Tubman guided the Bowley family from Baltimore to Philadelphia, likely traveling at night and using established Underground Railroad routes through Delaware and southeastern Pennsylvania.

The journey required careful planning to avoid slave catchers and law enforcement. James Alfred, age 6, remained in Philadelphia with Tubman to attend school while his parents and sister continued north.

Education was crucial for formerly enslaved people, and Tubman understood that James needed skills to succeed in freedom.

Tubman spent about half her income on James Alfred’s education during this period.

She worked as a domestic servant and cook in Philadelphia hotels, earning modest wages that she willingly shared to give her great-nephew opportunities she had never had.

The Fugitive Slave Act Changes Everything

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it dangerous for escaped slaves to remain in northern states.

This federal law was part of the Compromise of 1850, designed to appease Southern states by strengthening slavery enforcement nationwide.

The law required law enforcement officials in the North to aid in capturing escaped slaves, regardless of their personal beliefs about slavery.

It also denied accused fugitives the right to trial by jury and made it profitable for commissioners to rule in favor of slaveholders.

Tubman rerouted the Underground Railroad to Canada, where slavery was prohibited. British law had abolished slavery throughout its empire in 1833, making Canada a safe haven for American refugees from slavery.

The Family Reaches Freedom in Canada

The Bowley family made their way to Canada in 1851, settling in Chatham, Ontario.

Chatham became known as the “Black Mecca of Canada” because of its large population of formerly enslaved Americans who had escaped via the Underground Railroad.

Chatham had developed as a community for black fugitives from slavery, offering economic opportunities, schools for children, and a supportive community of people who understood the struggles of life after slavery.

The 1861 Census recorded the Bowley family in Canada with seven children total. John and Kessiah had built a successful life in freedom, with John continuing his work as a skilled craftsman and their children attending school.

Visiting Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park

The park is located at 4068 Golden Hill Road, Church Creek, Maryland 21622.

The 10,000-square-foot visitor center features multimedia exhibits about Tubman’s life and the Underground Railroad, plus a theater showing an introductory film.

You can explore exhibits about her childhood in slavery, her escape to freedom, and her work as a conductor. The center includes a gift shop and library.

Read More from This Brand:

Currently residing in Phoenix, Arizona with his wife and Pomeranian, Mochi. Leo is a lover of all things travel related outside and inside the United States. Leo has been to every continent and continues to push to reach his goals of visiting every country someday. Learn more about Leo on Muck Rack.

15 mountain towns in America where fall feels like a painting

This Connecticut submarine museum boasts the Cold War’s most desperate shopping trip

This Colorado town was literally built to shame its sinful neighbor

The drive that shows Maryland like you’ve never seen before

If You Understand These 14 Slang Terms, You’re Definitely from Arkansas

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania4 days ago

Pennsylvania4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina5 days ago

North Carolina5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine6 days ago

Maine6 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York5 days ago

New York5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina3 days ago

South Carolina3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio5 days ago

Ohio5 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia6 days ago

Georgia6 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story

New Hampshire6 days ago

New Hampshire6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New Hampshire Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else