New Jersey

New Jersey’s legal pirates: the Great Egg Harbor privateers

Published

2 months agoon

Great Egg Harbor’s Revolutionary War Privateer Fleet

The Great Egg Harbor River in New Jersey hides America’s most profitable secret weapon from the Revolutionary War. When Congress needed money and ships to fight Britain, they turned regular sailors into legal pirates.

These “privateers” could keep everything they stole from British merchants.

The river’s maze of hidden coves made perfect hideouts for citizen sailors who captured 600 enemy ships and cost Britain over $300 million in today’s money.

The story of how ordinary fishermen became wealthy raiders starts right here in these peaceful waters.

Congress Gave Privateers the Green Light in 1776

The Continental Congress passed a law on March 23, 1776 that changed everything for American sea captains. This law set up clear rules for privateering, letting private ship owners legally attack British vessels.

John Hancock signed papers on April 3, 1776, giving these citizen sailors permission to grab British ships and cargo. Ship owners put up money to make sure they followed the rules.

During the Revolutionary War, Congress gave out about 1,700 permission slips to nearly 800 different vessels.

Hidden Waterways Made Perfect Hideouts

George May built a shipyard and trading post near Babcock Creek in 1756, and people soon called the area May’s Landing.

The lower 10 miles of the Great Egg Harbor River led to the Atlantic Ocean, with countless hidden coves and twisting streams. These waterways created perfect hiding spots for privateers trying to avoid British warships.

Mays Landing grew into an important port and shipbuilding center with easy access to this river system.

American Sea Raiders Found Their Home Base

Privateers started using Great Egg Harbor and Little Egg Harbor rivers to launch attacks on British merchant ships by 1777.

After capturing British vessels, the privateers brought them back to these river ports to unload valuable cargo.

They moved goods upriver using flat-bottomed boats to The Forks, then loaded everything onto wagons bound for Washington’s army.

This river network became especially important during the harsh winter of 1777-1778 when Washington’s troops faced starvation at Valley Forge.

Privateering Turned Regular Sailors Into Wealthy Men

The Continental Congress made privateering very attractive by letting crews keep all the loot they captured from British ships. This created quick wealth for successful captains and their men.

By 1778, more than thirty well-armed American privateers patrolled the waters off New Jersey and New York.

These citizen sailors captured over 600 British ships throughout the war, causing about $18 million in damage to British shipping – about $302 million in today’s money.

British Leaders Got Fed Up With Constant Raids

General Clinton saw privateers as a major threat to British supply lines by summer 1778.

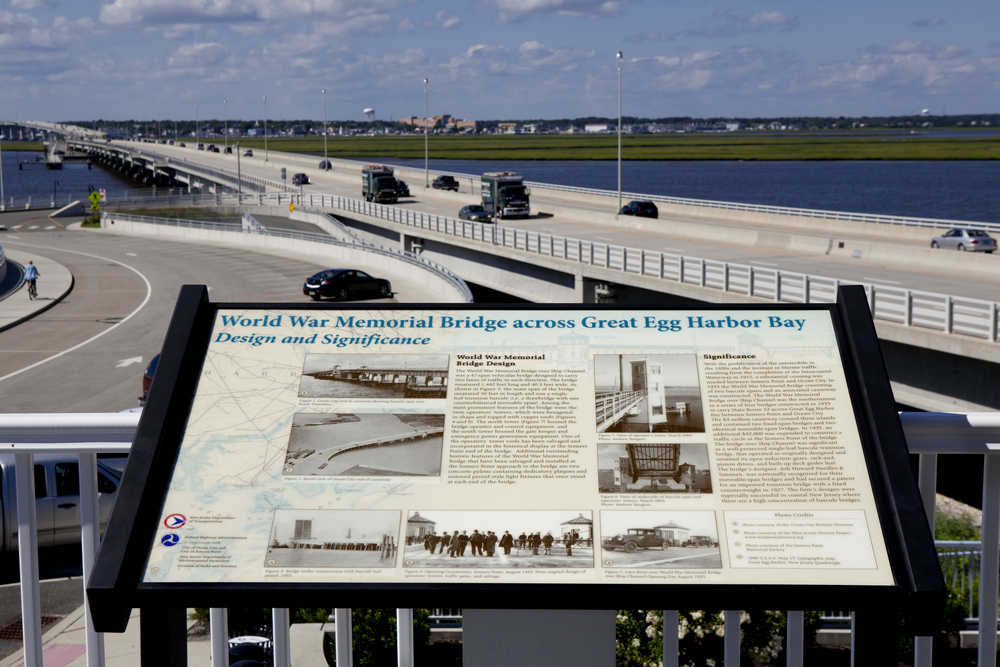

The last straw came when American privateers towed two fully loaded prize ships – the Venus and Major Pearson – into Little Egg Harbor. Workers quickly sent their valuable cargoes to support the rebel cause.

Clinton said he wanted to “clean out that nest of rebel pirates” operating from the river havens. British spies spotted Chestnut Neck as the main center for goods captured by privateers.

Royal Navy Sailed To Crush The Privateer Haven

Captain Henry Collins and Captain Patrick Ferguson led a mixed naval-army force from Staten Island on September 30, 1778.

Four hundred troops, including loyalist volunteers, boarded ships including HMS Zebra and sailed for New Jersey.

Bad weather slowed them down, turning a quick trip into a four-day journey before they reached Great Bay outside Little Egg Harbor River on October 5.

American lookouts spotted the British fleet and sent warnings, allowing three privateers to escape.

The British Burned Chestnut Neck To The Ground

British forces attacked a small American fort on the river with cannon fire from their ships on October 6, 1778. Local militiamen tried to defend the position but quickly ran into the woods after a brief fight.

The British then destroyed several privateer ships caught at anchor and burned down the village houses and warehouses that held captured British goods.

Stormy weather stopped the British from sailing farther upriver to catch more privateers at The Forks.

Pulaski’s Cavalry Showed Up A Day Late

General Casimir Pulaski arrived with his legion on October 8, one day after the British left Chestnut Neck. He set up camp about five miles northeast in Little Egg Harbor Township, ready to defend against more attacks.

Meanwhile, British ships sat trapped in Great Bay by bad weather for fifteen days, unable to return to their base. Ferguson’s raiders and Pulaski’s forces faced off as both sides waited for their next chance to strike.

A Traitor Revealed The Americans’ Position

Lieutenant Gustav Juliet ran away from Pulaski’s legion and joined the British, telling them exactly where to find the American camp and pointing out its poor security.

Ferguson loaded 250 men into boats on the evening of October 14 and rowed ten miles to Osborne Island. From there, his forces walked two miles through the darkness to reach the American outpost where fifty men slept.

The British got ready for a surprise attack at first light on October 15.

Bayonets In The Night Left Few Survivors

British loyalists stabbed nearly 50 sleeping American soldiers with bayonets in their dawn attack on October 15, 1778.

Ferguson’s men killed prisoners rather than capture them, a brutal move that earned the event its “massacre” label.

Pulaski heard the noise and rushed to the scene with his cavalry, forcing the British to run back to their boats. The Americans caught a few British stragglers but most got away.

People called it the Affair at Little Egg Harbor.

River Pirates Kept Hitting British Ships Despite Attacks

Despite the British raids, Great Egg Harbor privateers continued operating from the river system throughout the war.

Samuel Brown of Forked River built a gunboat called Civil Usage and patrolled Barnegat Bay looking for British targets.

River-based privateers like Captain Samuel Snell captured 19 British ships during the conflict, adding to the growing American tally.

The Great Egg Harbor’s complex waterways proved impossible for the British to fully control, allowing American privateers to maintain their operations until the war’s end.

These hidden river bases remained crucial to America’s maritime resistance strategy throughout the Revolutionary War.

Visiting Great Egg Harbor Scenic and Recreational River, New Jersey

You can explore Great Egg Harbor’s privateer history along 129 miles of designated river through the New Jersey Pinelands.

The Warren E.Fox Nature Center at Estell Manor Park on Route 50 has passport stamps and exhibits about these Revolutionary War citizen sailors.

Rent kayaks at Mays Landing to paddle the waterways where privateers once hid.

Walk the 1.8-mile Swamp Trail Boardwalk to see WWI ruins and an artesian well across 127,000 acres of free public lands.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

John Ghost is a professional writer and SEO director. He graduated from Arizona State University with a BA in English (Writing, Rhetorics, and Literacies). As he prepares for graduate school to become an English professor, he writes weird fiction, plays his guitars, and enjoys spending time with his wife and daughters. He lives in the Valley of the Sun. Learn more about John on Muck Rack.

Here Are 12 Things People from West Virginia Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Here Are 12 Things People from Washington Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Here Are 12 Things People from Virginia Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

New Mexico Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta wrap-ups and fall arts

Mississippi Natchez Trace fall festivals and music events

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania3 days ago

Pennsylvania3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina4 days ago

North Carolina4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Nebraska6 days ago

Nebraska6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Nebraska Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York4 days ago

New York4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina2 days ago

South Carolina2 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio4 days ago

Ohio4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia5 days ago

Georgia5 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story