Washington

How Lincoln’s 3-mile commute literally shaped the Emancipation Proclamation

Published

4 weeks agoon

Lincoln’s Daily Encounters with Escaped Slaves at Camp Barker

Abraham Lincoln’s daily ride from the Soldiers’ Home to the White House wasn’t just a commute. For three summers during the Civil War, he passed right through camps filled with escaped slaves.

Camp Barker, just a mile from the White House near today’s Logan Circle, held thousands who had fled to Union lines. Lincoln often stopped to talk with these “contraband of war,” as they were called.

He hired Mary Dines, a camp resident, as his cook and watched as she and others sang spirituals that moved him to tears.

These face-to-face meetings with people seeking freedom shaped his thinking as he wrote the Emancipation Proclamation.

The President Lincoln and Soldiers’ Home National Monument tells this hidden story of how a daily ride changed American history.

Three Enslaved Men Sparked a Revolution at Fort Monroe

Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend rowed across Hampton Roads in the dark on May 23, 1861. They reached Fort Monroe looking for freedom from their Confederate owner.

General Benjamin Butler refused to return them under the Fugitive Slave Act. He called Virginia a “foreign country” and named the men “contraband of war.”

Butler said that since Virginia left the Union, he didn’t need to return escaped slaves. Congress backed Butler with the First Confiscation Act on August 6, 1861.

News spread fast, and over 500 more slaves came to Fort Monroe within a month.

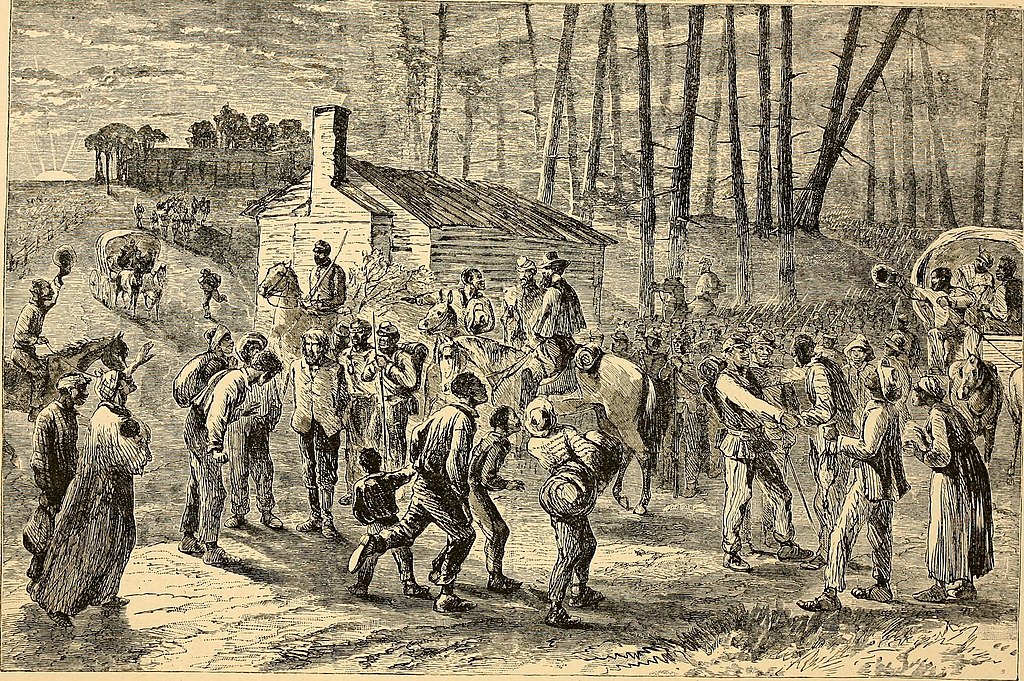

Freedom Seekers Doubled Washington’s Black Population

Thousands of former slaves came to Washington D.C. by early 1862. This doubled the city’s Black population to about 20,000.

Congress passed the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862, ending slavery in the capital and freeing over 3,000 slaves.

The government set up refugee camps throughout D.C. , including Camp Barker near today’s Logan Circle.

Camp life was hard but gave people education, religious freedom, community, and healthcare. Able-bodied refugees worked for the government or Union Army for housing and food.

Lincoln Family Escaped to Higher Ground After Willie’s Death

After 11-year-old Willie Lincoln died from typhoid fever in February 1862, Mary Lincoln needed to leave the sad White House.

The Lincoln family moved to the cottage at Soldiers’ Home in June 1862.

They wanted cooler air away from downtown Washington’s noise. The spot sat several hundred feet higher than the city, catching cool summer breezes.

The Lincolns stayed at Soldiers’ Home for three summers from 1862 to 1864. Lincoln rode to the White House daily for work.

Mary Lincoln called the cottage “a very charming place 2½ miles from the city.”

The President’s Commute Took Him Past Desperate Refugees

Lincoln’s three-mile horseback ride from Soldiers’ Home to the White House went right past Camp Barker. The camp stood just one mile from the Executive Mansion.

His route followed Rock Creek Church Road to Georgia Avenue, then Rhode Island Avenue to Vermont Avenue, passing Logan Circle where refugee headquarters operated.

Lincoln traveled with cavalry guards, though he sometimes snuck away alone before his escorts woke up.

Local people, including poet Walt Whitman who lived on Vermont Avenue, often greeted the president during his daily rides.

Aunt Mary Cooked for the First Family While Living in a Refugee Camp

Mary Dines, an escaped slave from Maryland, cooked for the Lincolns at their summer cottage and sometimes at the White House.

The Lincoln family called her “Aunt Mary.” She lived in a nearby refugee camp while working for America’s most famous family.

Dines had fled slavery hidden in a hay wagon, chased by dogs. She learned to read and write from her former owner’s children.

She became a leader at her camp, writing letters for other refugees and organizing community activities.

Lincoln Wiped Away Tears While Listening to Freedom Songs

Mary Dines told how Lincoln often stopped at refugee camps during his commute. He talked with refugees and heard their stories firsthand.

On at least two occasions, Lincoln visited camps just to hear “Negro spirituals” performed by choirs that Dines led.

During one performance, Dines saw Lincoln “wiping tears off his face with his bare hands” as refugees sang “Nobody Knows What Trouble I See, But Jesus.”

Lincoln joined in singing “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” his voice sounding “sweet” but “so sad.”

The Summer of 1862 Transformed Lincoln’s Thinking on Slavery

During summer 1862 at Soldiers’ Home, Lincoln started thinking about ending slavery as both a military need and moral duty.

He first talked about his early Emancipation Proclamation with cabinet members on July 13, 1862.

He read drafts to Secretary of State William Seward and Navy Secretary Gideon Welles. On July 22, 1862, Lincoln showed his draft to the full cabinet during a meeting.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton took notes of everyone’s reactions.

The Second Confiscation Act passed on July 17, 1862, gave Lincoln more legal power to free slaves as a war measure.

A Battlefield Victory Gave Lincoln His Moment to Act

After the Union won at Antietam, Lincoln felt ready to issue his warning to Confederate states.

On September 22, 1862, five days after Antietam and while staying at Soldiers’ Home, Lincoln called his cabinet together.

He issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, giving Confederate states until January 1, 1863, to return to the Union or face slave freedom.

The warning said that enslaved people in rebel areas would be “forever free” as of New Year’s Day 1863.

Face-to-Face Encounters Challenged Lincoln’s Earlier Racial Views

Lincoln’s regular visits to refugee camps gave him firsthand exposure to slavery’s human cost and freedpeople’s abilities.

Unlike most politicians who talked about slavery in theory, Lincoln saw the courage and dignity of freedom seekers every day.

Camp residents like Mary Dines showed formerly enslaved people’s smarts, leadership skills, and commitment to family and community.

Lincoln watched refugees help the Union war effort through labor, military service, and valuable information about Confederate movements.

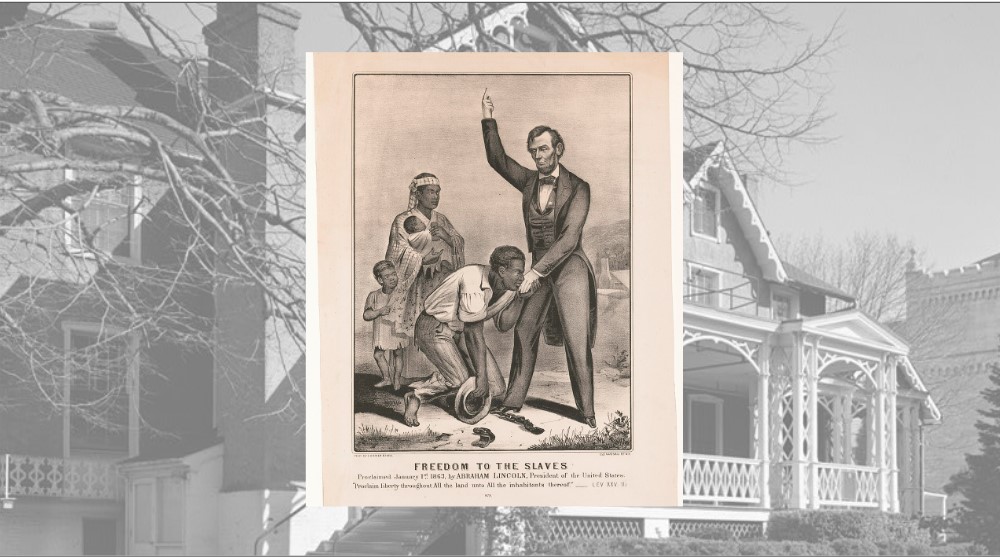

New Year’s Day Brought Freedom’s Promise to Millions

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the final Emancipation Proclamation, keeping his September promise to rebellious states.

The proclamation stated that enslaved people in Confederate territory “are, and henceforward shall be free.” It allowed African Americans to join Union military forces, turning former slaves into liberators.

The policy applied to about 3. 5 million enslaved people in rebellious states, though it left out loyal border states and Union-controlled areas.

Contraband camps celebrated “Jubilee Day” with cannon shots, church bells, and public readings of the proclamation.

The Daily Ride That Changed American History Continued Until 1865

Lincoln kept up his daily commutes past contraband camps through 1864. This maintained his personal connection to the human side of emancipation.

His last visit to Soldiers’ Home happened the day before his assassination on April 14, 1865.

Mary Lincoln later remembered how “dearly I loved the Soldiers’ Home” and the meaningful experiences the family had there.

Lincoln’s daily meetings with freedom seekers gave him a unique presidential perspective on slavery’s realities and African Americans’ potential.

The contraband camp experiences influenced Lincoln’s evolving views toward racial equality and post-war Reconstruction policies.

Visiting President Lincoln and Soldiers’ Home National Monument, Washington

You can visit President Lincoln and Soldiers’ Home National Monument at 140 Rock Creek Church Road NW to learn about Lincoln’s daily three-mile commute past contraband camps that influenced the Emancipation Proclamation.

Buy tickets ahead since hourly tours from 10am to 3pm sell out quickly. The one-hour cottage tours include multimedia experiences and run 362 days yearly.

You’ll need government ID to enter the Armed Forces Retirement Home grounds. Free admission available through Museums for All.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

John Ghost is a professional writer and SEO director. He graduated from Arizona State University with a BA in English (Writing, Rhetorics, and Literacies). As he prepares for graduate school to become an English professor, he writes weird fiction, plays his guitars, and enjoys spending time with his wife and daughters. He lives in the Valley of the Sun. Learn more about John on Muck Rack.

Here Are 12 Things People from West Virginia Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Here Are 12 Things People from Washington Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Here Are 12 Things People from Virginia Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

New Mexico Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta wrap-ups and fall arts

Mississippi Natchez Trace fall festivals and music events

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania3 days ago

Pennsylvania3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina4 days ago

North Carolina4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Nebraska6 days ago

Nebraska6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Nebraska Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York4 days ago

New York4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina2 days ago

South Carolina2 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio4 days ago

Ohio4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia5 days ago

Georgia5 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story