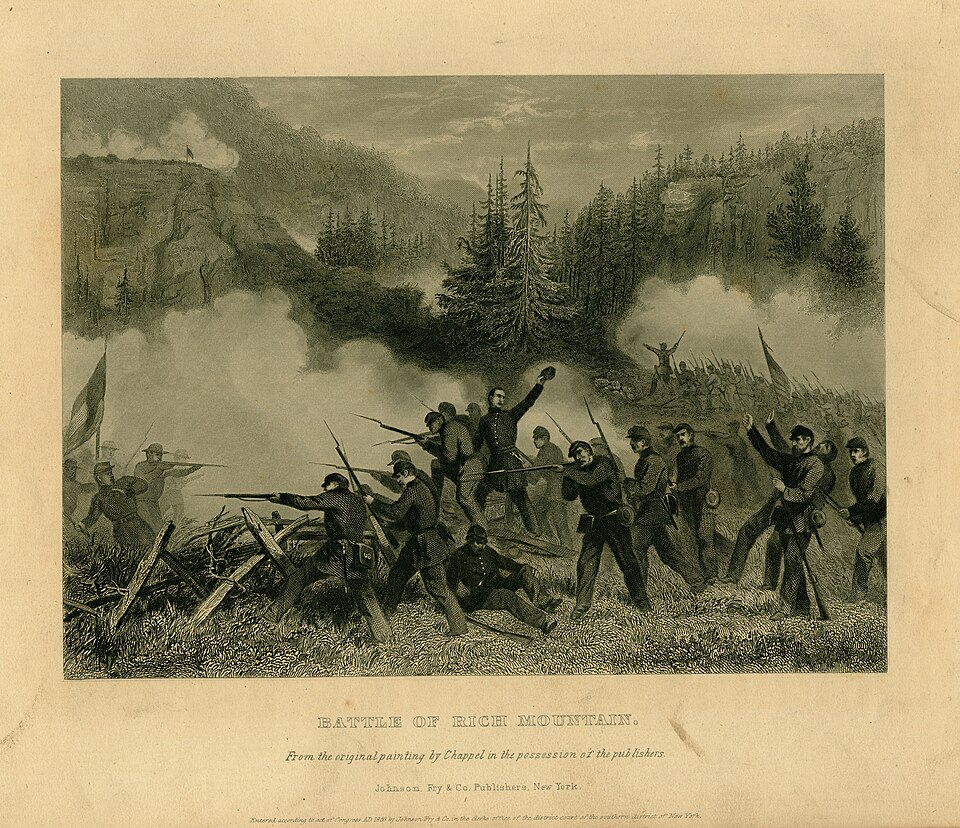

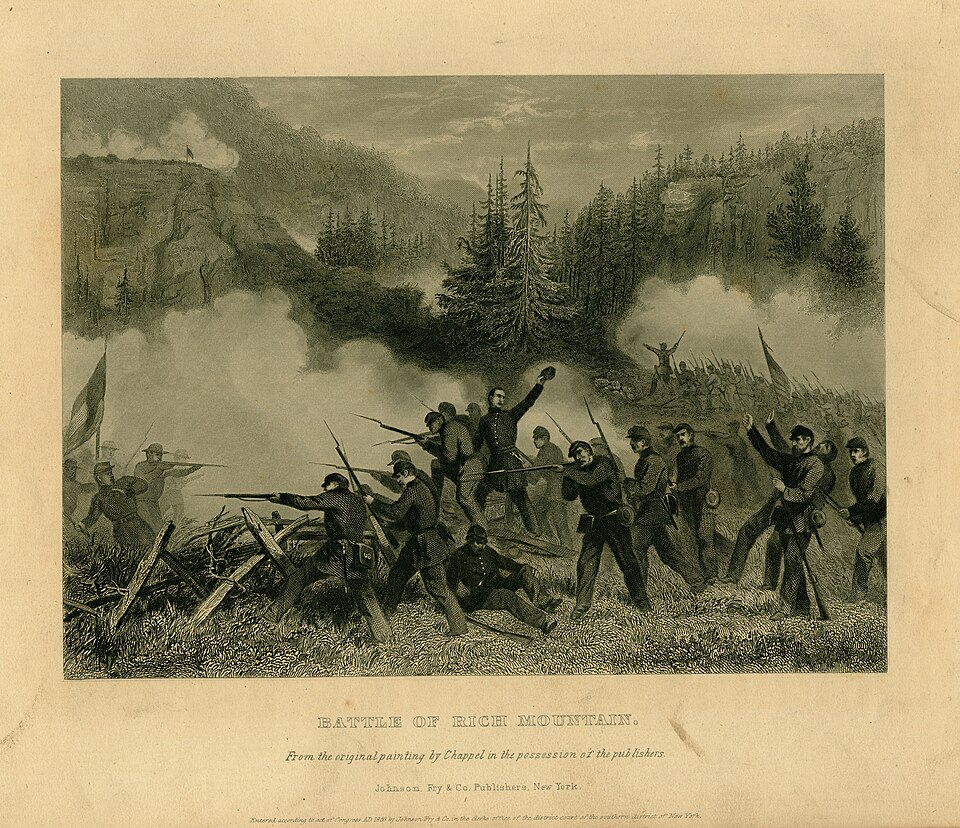

Wikimedia Commons/Alonzo Chappel

Robert Garnett’s Fatal Last Stand at Corrick’s Ford

Robert Garnett knew he was in trouble from the start.

“They have not given me an adequate force,” he warned before taking command in western Virginia in 1861. He was right.

After Union troops beat his men at Rich Mountain on July 11, Garnett led 4,500 soldiers on a desperate midnight retreat.

Two days later at Corrick’s Ford, as rain pounded down and the Cheat River rose, he stayed with his rear guard. “The post of danger is now my post of duty,” he told those urging him to flee.

Moments later, a Union bullet struck him in the back. The Civil War had claimed its first general.

Today, Rich Mountain Battlefield preserves the earthworks where this tragic story began.

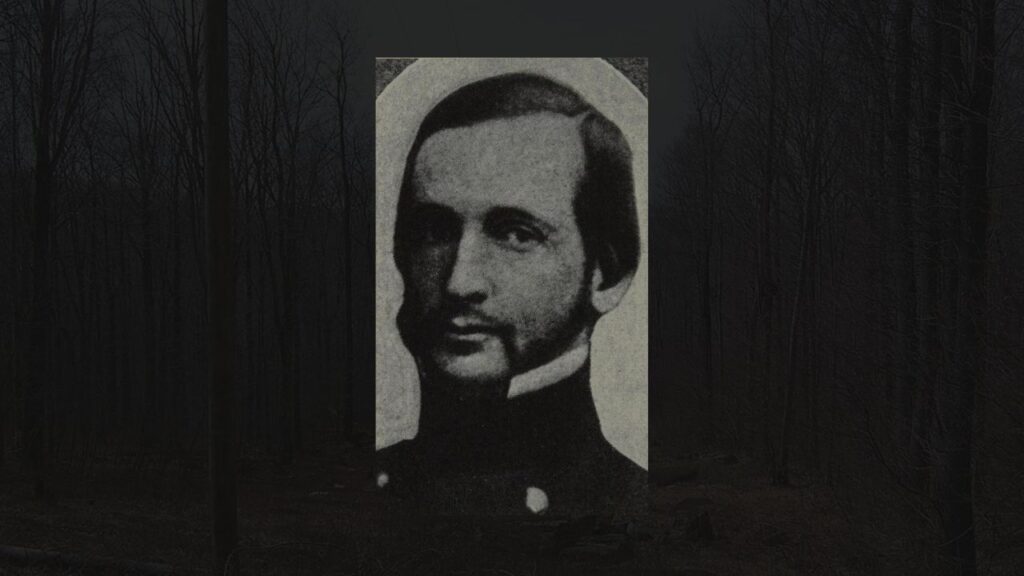

Wikimedia Commons/Ooligan

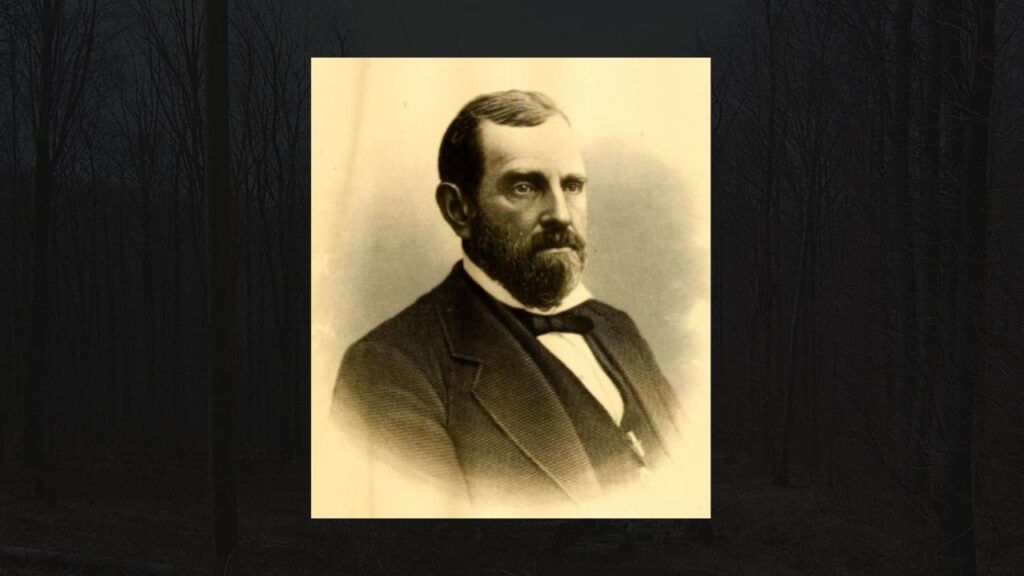

A Virginia Plantation Boy Destined for Military Fame

Robert Garnett was born December 16, 1819, at Champlain plantation in Essex County, Virginia. He grew up with six siblings in a politically connected family.

His dad served five terms in Congress, while his mom came from French playwright roots. Young Robert went to Norfolk Academy, where he studied engineering, drawing, and became great at horseback riding.

His cousin Richard would later die at Gettysburg during Pickett’s Charge.

Wikimedia Commons/American Battlefield Protection Program

His West Point Days Shaped His Military Career

Robert joined the U.S. Military Academy on September 1, 1837, alongside his cousin Richard. Four years later, he graduated 27th out of 52 cadets.

Seven of his classmates later died fighting in the Civil War, but on different sides.

After graduation, the Army made him a second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Artillery and sent him to guard the Canadian border, where tensions still bubbled from earlier disputes.

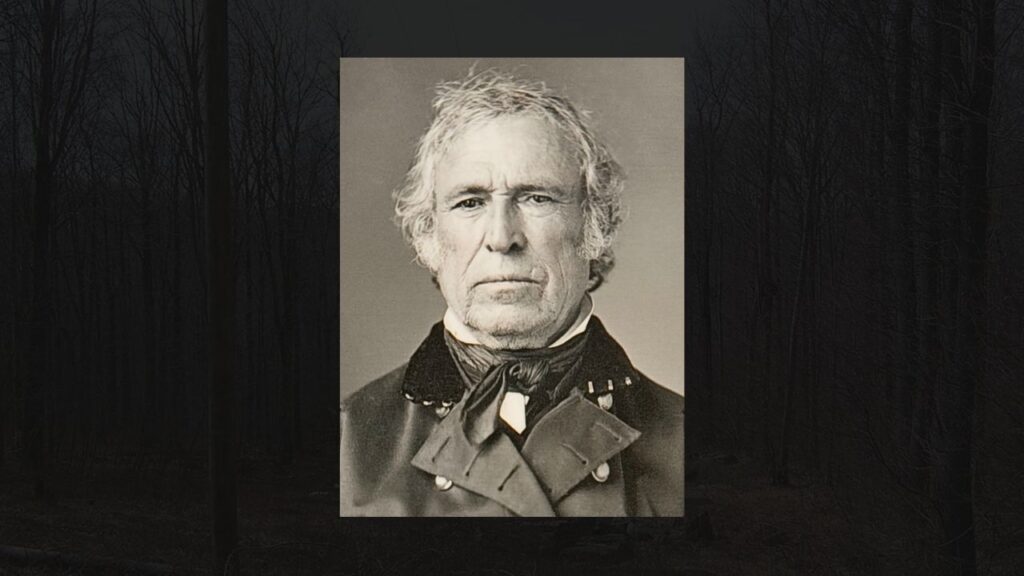

Wikimedia Commons/Beao

Mexican War Heroics Earned Him Quick Promotions

The young officer worked under General Zachary Taylor during the Mexican-American War as his personal aide. He fought bravely at Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Buena Vista.

The Army rewarded his courage with two quick promotions: captain for bravery at Monterrey and major for his outstanding conduct at Buena Vista.

After the war, Garnett stayed on as Taylor’s military advisor, building helpful connections.

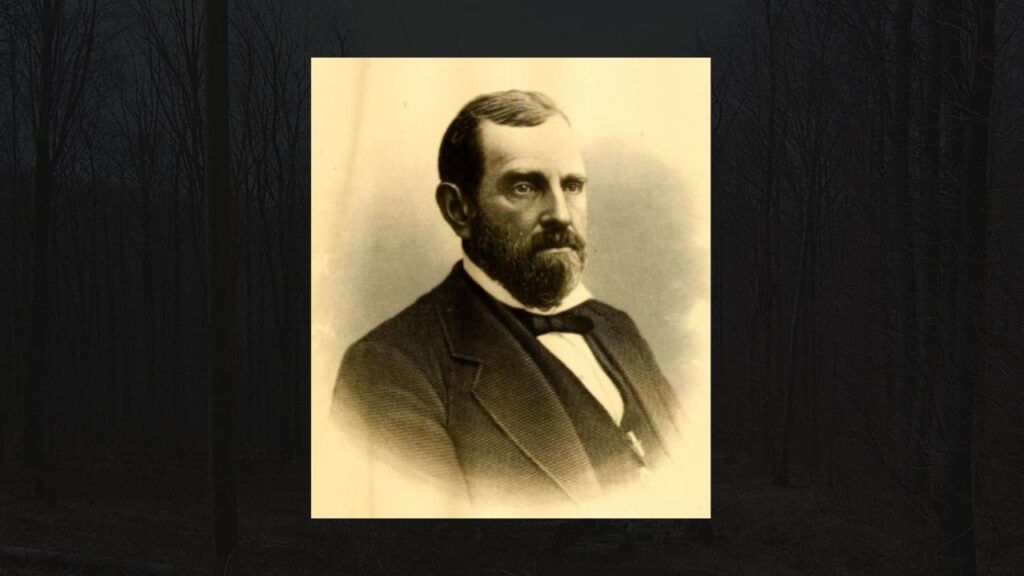

Wikimedia Commons/Tobias Kleinlercher / Wikipedia

The California Seal Designer Headed West

The Army sent Garnett to deliver important papers to San Francisco in 1849. During his trip, he drew the design that became the Great Seal of California.

His artistic skills and military presence got noticed, and he later worked as Commandant of Cadets at West Point from 1852-1854 under Robert E. Lee.

The Army then promoted him to major of the 9th U.S. Infantry and sent him to Washington Territory.

Wikimedia Commons/Rosenthal, James W., creator

Heartbreak at Fort Simcoe Changed Him Forever

Garnett married Marianna Nelson from Boston on January 24, 1857. Their son Arthur was born in February 1858 at Fort Simcoe in Washington Territory.

But tragedy hit in September 1858 when his wife caught a fever and died on the 17th. Just six days later, their baby son also died.

After burying his family in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, a heartbroken Garnett took a long trip to Europe, trying to escape his grief.

Wikimedia Commons/Julian Vannerson

The Confederacy Gave Him a Doomed Assignment

When the Civil War started, Garnett rushed back from Europe and quit the U.S. Army in April 1861. The Confederacy made him adjutant general under Robert E. Lee, then promoted him to brigadier general on June 6, 1861.

His new job put him in charge of Northwestern Virginia with orders to protect key railroads and roads.

Before leaving, he made a grim prediction: “They have not given me enough men. They have sent me to my death.”

Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Outnumbered Defenders Faced Impossible Odds

Garnett placed his 4,600 Confederate troops at key spots along the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. His small force faced a huge Union army of over 20,000 soldiers led by Major General George McClellan.

Garnett put his men at Rich Mountain and Laurel Hill to guard vital supply routes.

He knew his smaller numbers made winning almost impossible against McClellan’s massive force, but he followed orders and set up his defenses.

Wikimedia Commons/Brady National Photographic Art Gallery

A Midnight Retreat Through Mountain Wilderness

Union forces under General William Rosecrans outflanked Confederate positions at Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861. After this loss, Garnett left Laurel Hill around midnight with 4,500 men.

Bad luck struck when he got wrong information that Union troops blocked Beverly, forcing him to take a longer, more dangerous route.

His tired column crossed Cheat Mountain into the Cheat River Valley while Union forces chased them through rough terrain and bad weather.

Wikimedia Commons/George Edward Perine

His Last Stand Came at a Swollen River Crossing

Union General Thomas Morris caught up with Garnett’s rear guard at Corrick’s Ford on the rain-swollen Cheat River on July 13.

Garnett personally led the rear guard action to slow down the Union attack and protect his retreating main column. When officers urged him to get to safety, he refused: “The post of danger is now my post of duty.”

Confederate sharpshooters from the 23rd Virginia fought hard behind driftwood along the riverbank as Garnett directed their defense.

Wikimedia Commons/Clyde Jimpson of the Arkansas String Beans

A Single Shot Made Civil War History

As Garnett turned in his saddle to order his men to withdraw, Sergeant R.F. Burlingame of the 7th Indiana Regiment fired a shot that struck him in the back.

The general fell from his horse and died almost instantly, becoming the first general officer killed in the Civil War.

His retreating soldiers left behind their commander, one cannon, and nearly 40 wagons in their haste to escape.

Major John Love, Garnett’s old West Point roommate who fought for the Union, arrived and identified his friend’s body.

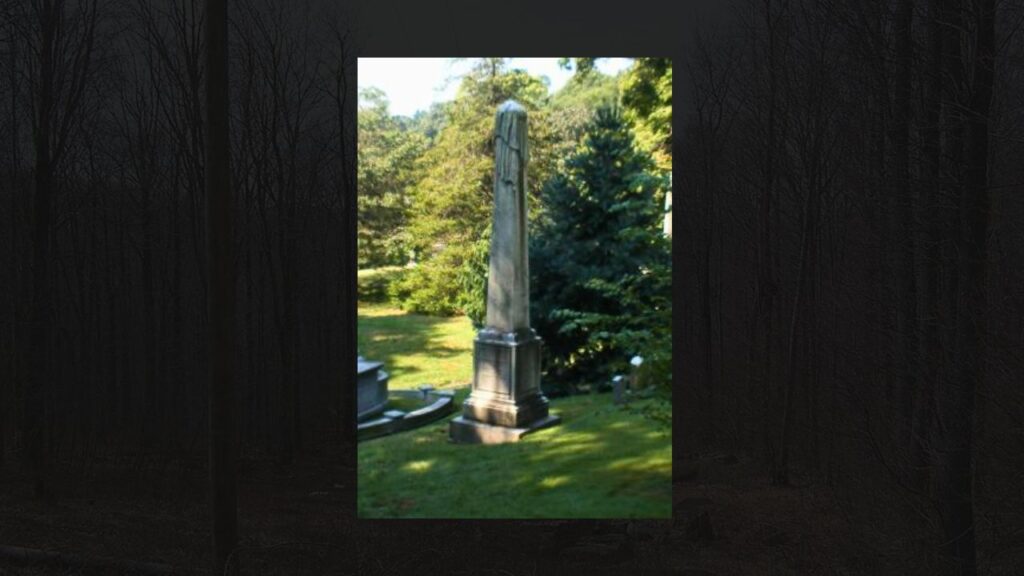

Wikimedia Commons/Sarnold17

Former Comrades Honored Their Fallen Enemy

Federal officers arranged a military honor guard to return Garnett’s body under a flag of truce, recognizing his earlier service in the Mexican War.

His family first buried him in Baltimore before moving him next to his wife and child in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

His grave monument features three faces mentioning his wife and son, with the words “To My Wife and Child” carved in stone. The fourth face remains blank.

Confederate General E. Porter Alexander later wrote that Garnett would have become one of the South’s greatest generals had he lived.

Wikimedia Commons/Bitmapped

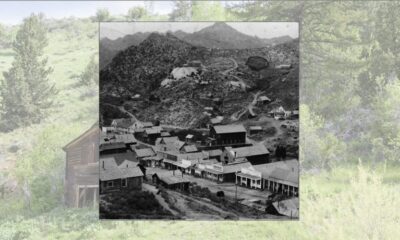

Visiting Rich Mountain Battlefield, West Virginia

Rich Mountain Battlefield is 5 miles west of Beverly on Rich Mountain Road and free to visit dawn to dusk year-round.

Start at Beverly Heritage Center on Court Street for directions and background about General Garnett’s death at nearby Corrick’s Ford. The center costs $5 and opens Tuesday-Sunday 10am-5pm.

Self-guided trails connect the mountaintop battlefield to Camp Garnett below, and gravel road sections follow the original 1860s Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike route.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

Kansas5 days ago

Kansas5 days ago

West Virginia4 days ago

West Virginia4 days ago

Alabama4 days ago

Alabama4 days ago

Idaho4 days ago

Idaho4 days ago

Alabama3 days ago

Alabama3 days ago

Kentucky5 days ago

Kentucky5 days ago

West Virginia4 days ago

West Virginia4 days ago

Alaska4 days ago

Alaska4 days ago