West Virginia

Meet the blind teacher who defied politicians and built West Virginia’s first disability school in Romney

Published

4 minutes agoon

Howard Johnson’s Fight for West Virginia’s Deaf School

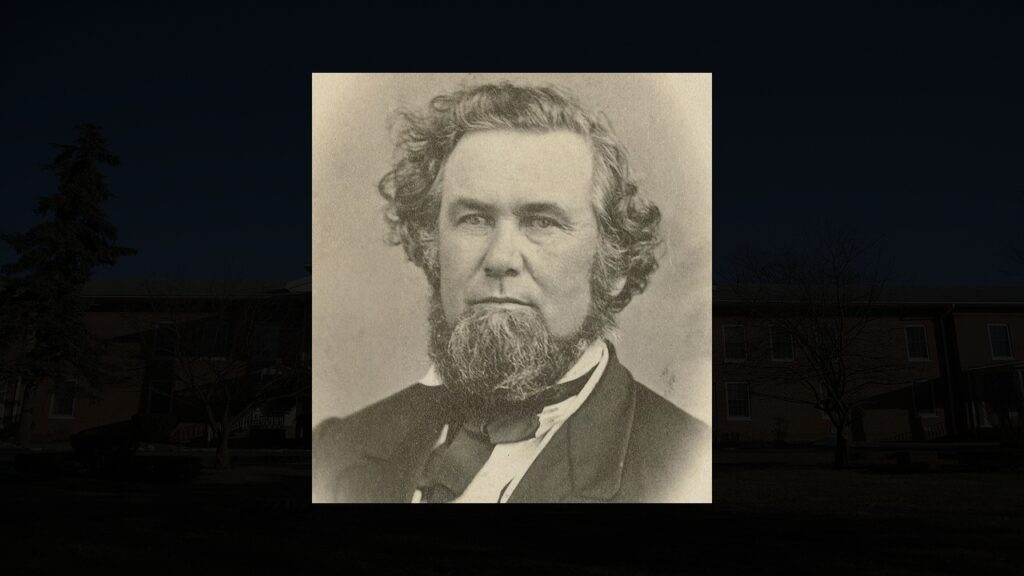

In 1869, a young blind teacher named Howard Johnson took on West Virginia’s most powerful men.

The new state paid to send deaf and blind kids to schools in other states, but Johnson had a bold plan: build their own school. Politicians laughed and told him he would fail.

Yet Johnson kept going, wrote to the governor, and won public support across the state. By March 1870, his dream became law.

The Romney community pitched in $1,383 from 118 donors, and the school opened that fall. The historic Romney district still stands today as proof that one man’s vision changed thousands of lives.

A Blind Teacher’s Bold Dream Changed West Virginia Forever

Howard Hille Johnson, a 24-year-old blind teacher from Pendleton County, spotted a big problem in 1869. West Virginia’s deaf and blind kids couldn’t go to the Virginia School in Staunton after becoming a state in 1863.

The state paid for some children to attend schools in nearby states, but most got no education at all. Johnson knew what good schooling could do for blind people like himself.

He went to that Virginia school and became a teacher.

Letters to the Governor Kicked Off a Movement

Johnson started writing to Governor William E. Stevenson in early 1869.

He shared his big idea for a state school for blind children. The governor wrote back quickly, promising to support Johnson’s plan.

This backing from the state’s top official gave Johnson the push he needed to take his campaign further. His time at the Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind taught him exactly how these schools should run.

Traveling Across Mountains to Win Hearts and Minds

Johnson hit the road, traveling all over West Virginia to build support.

He visited towns big and small, talking to folks about why deaf and blind children needed proper schooling. People listened.

Many were shocked to learn these children had no options after statehood. Johnson’s grassroots campaign grew stronger with each stop.

The public support he built helped get politicians on board with his plan.

Politicians Tried to Crush His Dreams

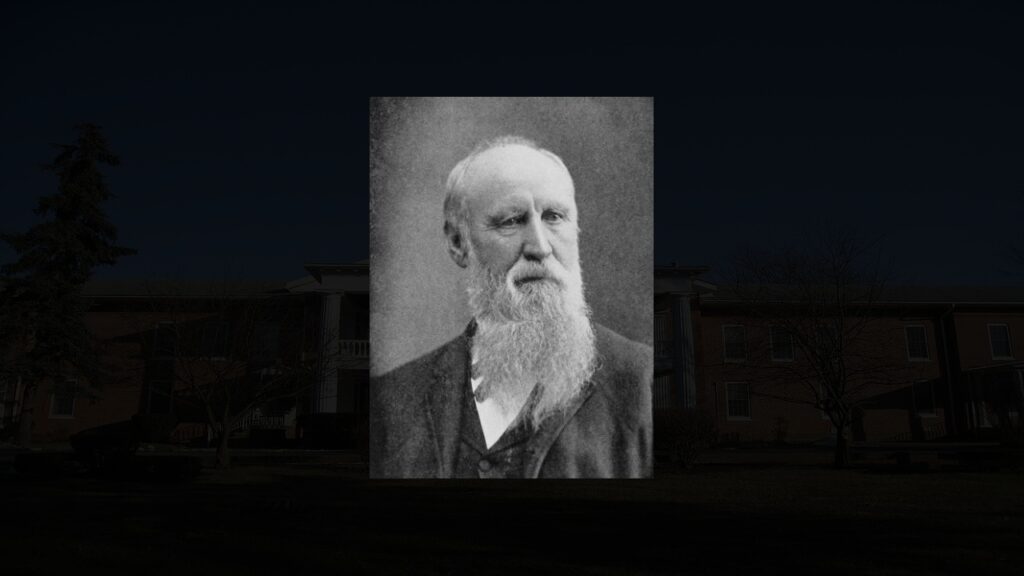

Not everyone backed Johnson’s plan. Former Union Governor Francis Harrison Pierpont told Johnson in Fairmont that he “could not afford to connect his name with an enterprise so sure to fail. ”

Joseph S. Wheat, a delegate from Morgan County, said the bill would flop because West Virginia couldn’t afford another public institution. These harsh words from powerful men didn’t stop Johnson, who kept pushing forward.

Showing Off What Blind Students Could Do

Johnson came up with a clever plan to win over doubtful lawmakers. He staged a show right in the House of Delegates chamber.

Johnson, his brother James, and Susan Ridenour – all blind – played music, recited poetry, and showed off classroom skills. The legislators watched as these blind individuals proved they could learn and achieve.

This performance changed minds and hearts, turning many doubters into supporters.

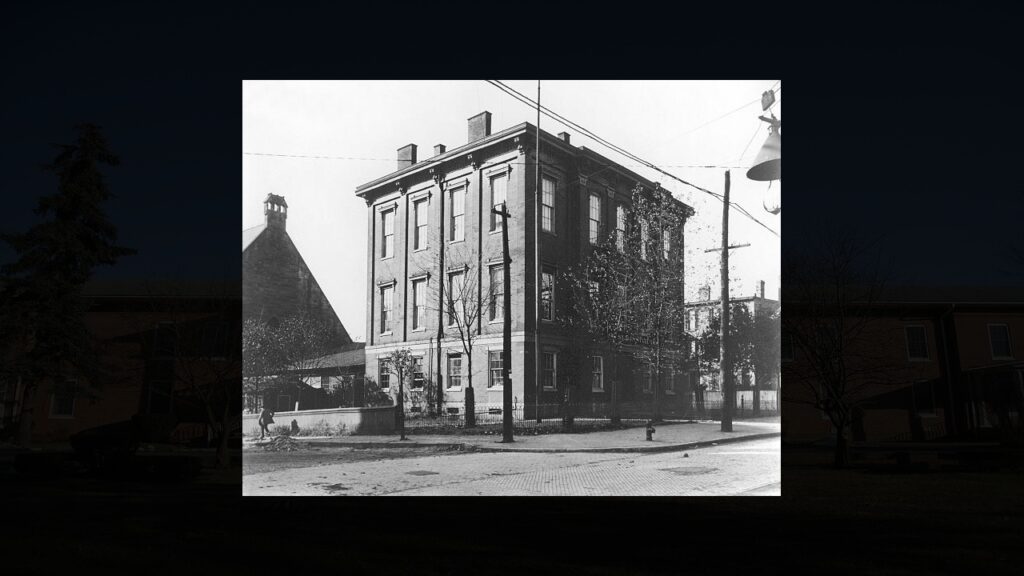

Lawmakers Finally Took Action in Wheeling

The West Virginia Legislature met in Wheeling, then the state capital, on January 18, 1870. Thanks to Johnson’s hard work, lawmakers proposed a bill to create a school for blind students.

Johnson’s months of travel, talks, and demonstrations paid off.

The bill got serious attention from the start, with strong backing from both citizens and some key politicians.

One Smart Change Made the School Even Better

House Delegate James Monroe Jackson from Wood County suggested they should include deaf students in the school too. Johnson quickly supported this idea, seeing it as both “humane and economic.”

This approach matched what other states did at the time, putting deaf and blind education under one roof. The change passed easily, making Johnson’s vision bigger and more inclusive than he first planned.

The Dream Became Real on a March Day

Success came on March 3, 1870, when the legislature passed the act creating the West Virginia Institution for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind. Governor Stevenson signed it into law.

The law welcomed “all deaf and dumb and blind youth” in West Virginia between ages six and twenty-five.

West Virginia historians credit Johnson, just 24 years old, as the founder of these schools that would help countless lives for generations.

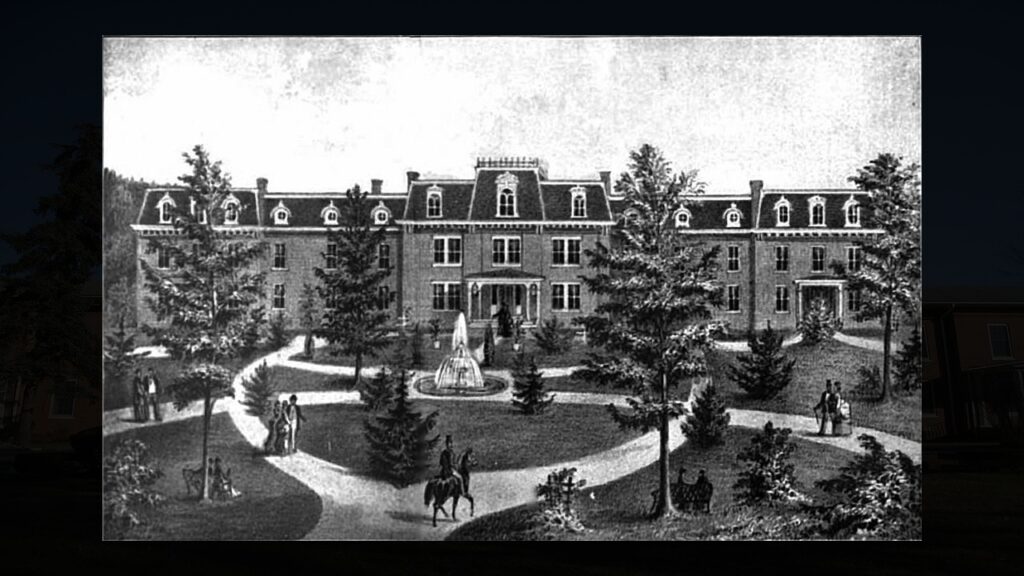

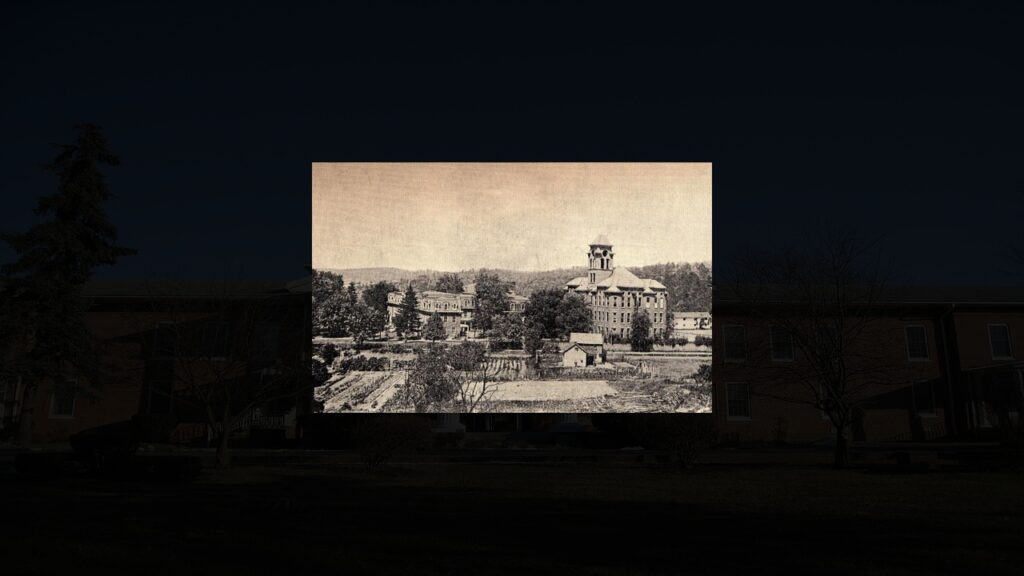

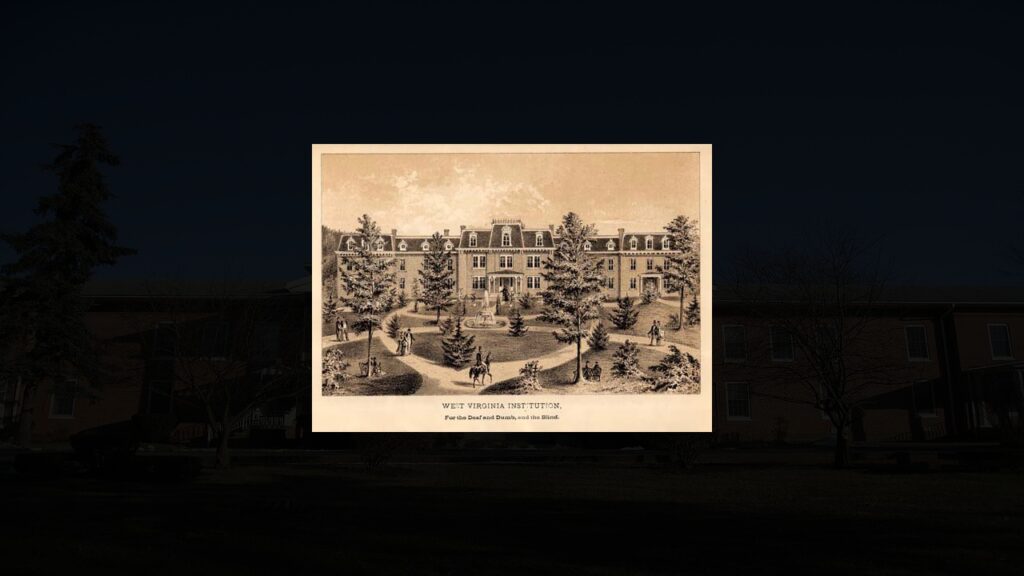

Three Towns Competed to Host the New School

Governor Stevenson put Johnson on the school’s first Board of Regents, which met in Wheeling on April 20, 1870. The board announced a contest to decide where to build the school.

Wheeling, Parkersburg, and Romney all made offers.

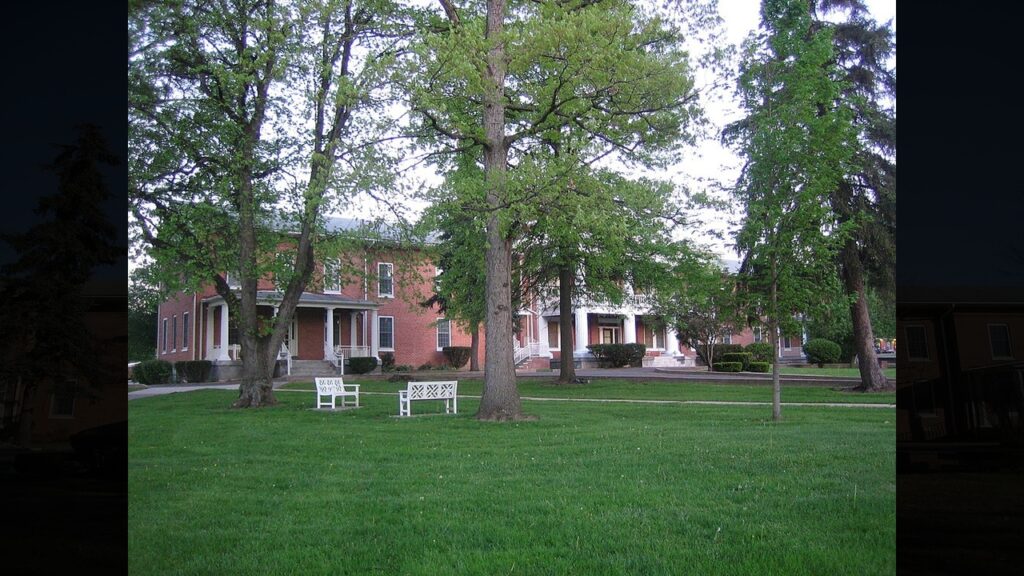

Romney won when the Romney Literary Society offered to donate the buildings and grounds of the closed Romney Classical Institute, worth $20,000.

Small-Town Folks Pitched In During Hard Times

The Romney Literary Society needed to raise over $1,000 to finish the property transfer, a tough task during Reconstruction.

On July 11, 1870, the Board of Regents asked for between $1,200 and $1,300 to complete the deal. The community stepped up in a big way.

A total of 118 individuals and businesses donated $1,383. 60.

The society also put in $320 for repairs to get the old Romney Classical Institute buildings ready for students.

Doors Opened to Students That Fall

The West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind welcomed its first students on September 29, 1870. Thirty kids showed up that first day – twenty-five deaf and five blind.

Johnson joined the inaugural Board of Regents and got the job of principal teacher for the blind department. He taught blind students at the school for 43 years until he died in 1913.

The young man’s vision had created an institution that would serve West Virginia’s children for centuries to come.

Visiting Romney Historic District, West Virginia

You can explore Romney’s connection to Howard Johnson’s campaign for the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind at several historic sites.

The 79-acre campus houses the schools, though the Administration Building burned in 2022. Visit Taggart Hall Civil War Museum at 91 South High Street by calling 681-231-2400 for appointments.

The Davis History House offers tours spring through October via Hampshire County Public Library, and the Wilson-Wodrow-Mytinger House at 51 West Gravel Lane dates back to the 1750s.

This article was created with AI assistance and human editing.

Read more from this brand:

John Ghost is a professional writer and SEO director. He graduated from Arizona State University with a BA in English (Writing, Rhetorics, and Literacies). As he prepares for graduate school to become an English professor, he writes weird fiction, plays his guitars, and enjoys spending time with his wife and daughters. He lives in the Valley of the Sun. Learn more about John on Muck Rack.

Meet the blind teacher who defied politicians and built West Virginia’s first disability school in Romney

Why did it take 17 years and one stubborn Ohioan to build this WWII memorial?

Arkansas’s DeGray Lake preserves memories a French-Caddo friendship that lasted generations

This Alaska fort imported Italian craftsmen to build America’s northernmost military palace

The Confederate high society once danced toward disaster at this Alabama house

12 Reasons Why You Should Never Ever Move to Florida

Best national parks for a quiet September visit

In 1907, Congress forced Roosevelt to put God back on U.S. coins. Here’s why.

The radioactive secret White Sands kept from New Mexicans for 30 years

America’s most famous railroad photo erased 12,000 Chinese workers from history

Trending Posts

Pennsylvania3 days ago

Pennsylvania3 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Pennsylvania Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

North Carolina4 days ago

North Carolina4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from North Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Nebraska6 days ago

Nebraska6 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Nebraska Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Maine5 days ago

Maine5 days agoThe ruins of a town that time forgot are resting in this Maine state park

New York4 days ago

New York4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from New York Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

South Carolina2 days ago

South Carolina2 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from South Carolina Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Ohio4 days ago

Ohio4 days agoHere Are 12 Things People from Ohio Do That Seem Insane To Everyone Else

Georgia5 days ago

Georgia5 days agoThis plantation’s slave quarters tell Georgia’s slowest freedom story